John Cassidy at the New Yorker writes a “review article”: “Is Larry Summers really right about inflation?” I found the following paragraph enlightening:

Goolsbee also claimed, however, that Summers’s analysis of why inflation could reëmerge, which he has doubled and tripled down on over the past twelve months, hasn’t necessarily been borne out by events.

Whereas Summers emphasizes the role that Biden’s American Rescue Plan played in stimulating demand throughout the economy, and the failure of the Fed to react quickly enough to rising prices, Goolsbee and others emphasize pandemic-related factors, particularly the impact of the coronavirus on global supply chains and the American labor market.

“This distinction has been lost in the popular political debate, where the fact of high inflation overshadows everything,” Goolsbee said. “But it does matter for thinking through how to respond going forward.”

It must be said that Summers was not alone, in Spring 2020, to pander about rising inflation in the horizon. While Summers focused on fiscal causes (American Rescue Plan), others, like Tim Congdon & Steve Hanke, old style monetarists, emphasized the record money growth that was ongoing.

Here, I´ll try to bring back the “lost distinction” about inflation. To economize on words that may be hard to disentangle, I´ll illustrate with charts comparing 5 countries. We´ll see that “everywhere” inflation has gone up. They have done so by different magnitudes that relate closely to the conduct of monetary policy.

Note that in the Eurozone countries (Germany, Italy & Spain), although monetary policy is conducted for all by the European Central Bank (ECB), the chosen policy has differing impacts in the different countries.

Of the 5 countries examined, we observe that only the US can be “accused” of adopting an “expansionary monetary policy”, but doing so only in mid-2021.

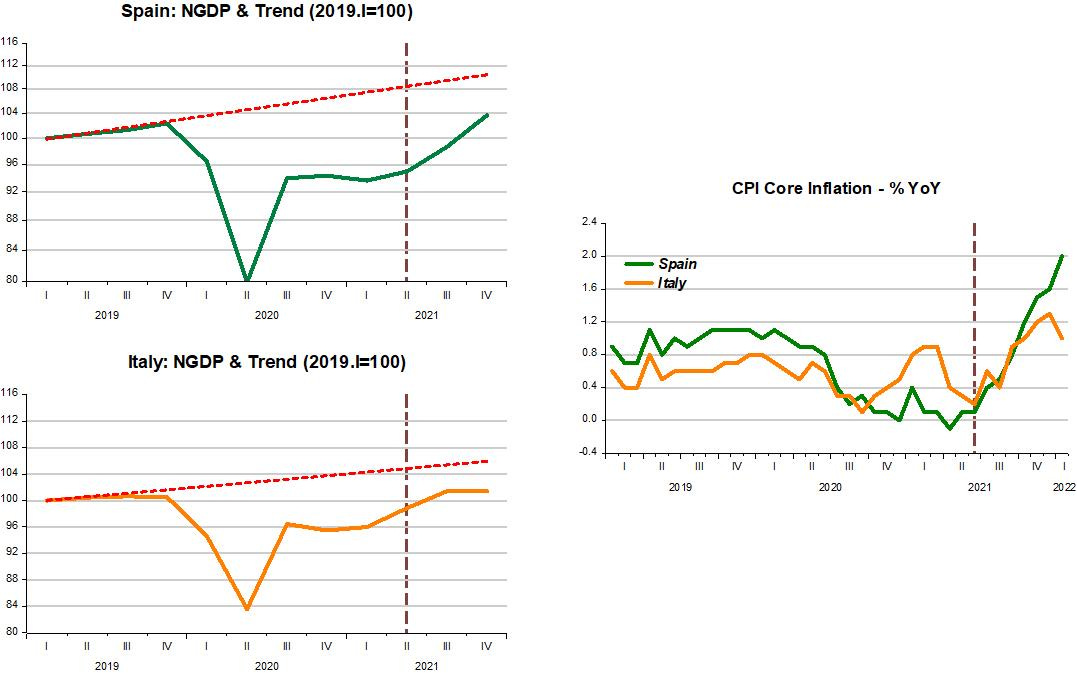

The first set of charts compares Spain and Italy. "(For all the NGDP & Trend charts the scale is same, with the NGDP index set at 100 in the first quarter of 2019).

Note that Spain´s NGDP fell the most at the outset of the pandemic. Inflation dropped from already low levels. In Italy inflation turns around quickly. Remember that Italy was the country initially most affected by Covid-19, with lockdowns quickly implemented. In both countries, NGDP turned around quickly (that fact is present in all cases I examine).

NGDP levels off quickly, so while in Spain inflation remains low, in Italy it recoils somewhat after having risen due to supply constraints from supply disruptions.

When NGDP goes up again, supply restrictions quickly bind and supply induced inflation climbs! With aggregate nominal demand (NGDP) rising faster in Spain, inflation there goes up more. While NGDP remains below the trend path it was on before the pandemic, all the inflation observed is due to supply restrictions.

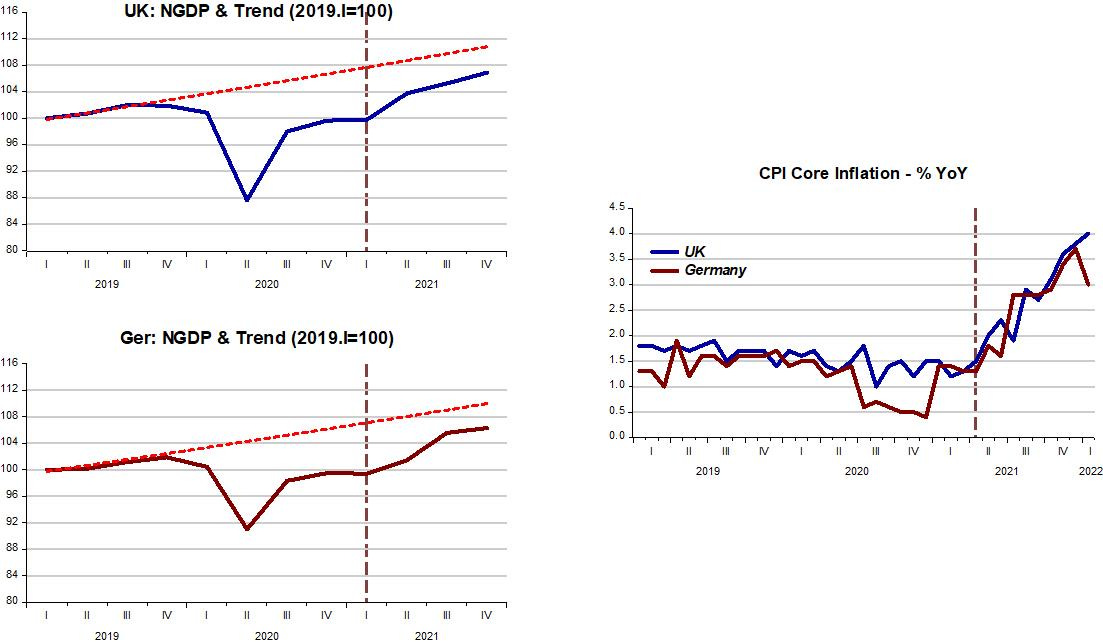

The next chart contrasts the UK & Germany. NGDP in the UK fell more than in Germany, but while inflation in Germany fell, it did not move much in the UK. We could infer that supply restrictions hit Britain more rapidly.

When NGDP climbs again in both countries, supply constraints bind and inflation picks up. Interesting to note, looking at Germany and Italy, when NGDP flattens, inflation turns down!

Again, in the UK & Germany, the factor behind the increase in inflation is Not demand, but supply constraints. The dynamic AS/AD model tells us that the best the central bank can do faced with a supply shock is to keep AD (NGDP) growing stably along its trend path. In the cases examined so far, demand is still short (of the trend).

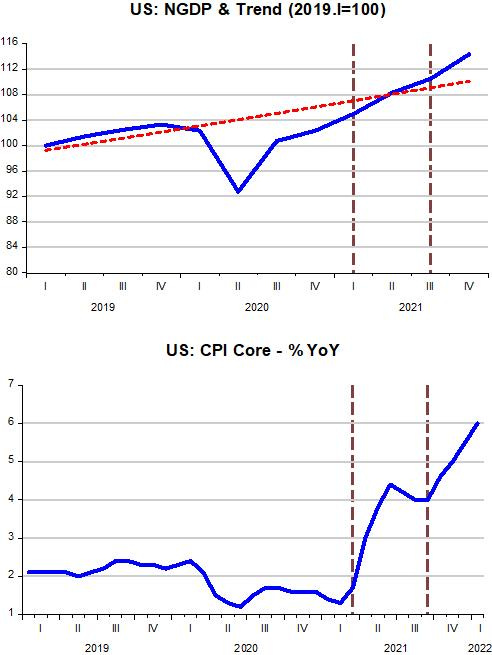

The argument is “closed” when I examine the case of the US. Compared to the other countries, in the US NGDP fell less (meaning monetary policy (not fiscal policy) was more “proactive”. And continued to be so because NGDP rose faster, quickly reaching the trend path it was on before the Covid-19 shock hit!

Between the two vertical lines, NGDP remained close to trend, so all of the increase observed in inflation was due to supply constraints. But then, the Fed “erred”, allowing NGDP to climb above trend. The increase in inflation from that point is demand induced (again, not from fiscal largesse, but from monetary expansion).

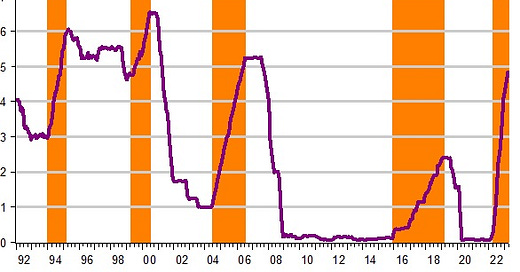

In the US, now, the Fed is on the “hot seat”. My standing suggestion is not that it “tightens the screws” to bring inflation down (more precisely act so as to bring NGDP quickly back to trend, which would turn the “demand-induced” inflation back down, but to more “gently” nudge NGDP back to trend on a “horizontal” instead of “vertical” fashion, as illustrated in the chart below, which depicts monthly NGDP from Macroeconomic Advisers.

To do that, the Fed will have to “exactly” offset changes in velocity (which has become more uncertain due to the War) with opposing changes in money supply in order to keep NGDP “constant” and as close as possible to 24 trillion. Year on year growth of NGDP will keep falling to the 4% growth trend path as illustrated in the picture. After that the Fed should try to keep NGDP rising along the trend path. With the waning of supply restrictions, inflation will go back to around the 2% target.

Is that possible? Yes. Will the Fed manage the “trick”? As the Beach Boys would say: “God only knows”

I asked this before but I don’t think I explained well what I meant. Nominal US GDP is $24 T. You want it to stay there for say 3-4 quarters. Let’s use 4 - easier math but note negative impacts less if only 9 months. If inflation immediately dropped to the 2% as stated, that would imply real growth at -2% so pretty garden variety recession. Am I missing anything? Thanks!

What data indicates fiscal policy and resulting boost to consumer and business cash didn’t influence US inflation. Why can’t supply disruptions, monetary expansion, and fiscal all be material contributions?