Sometimes monetary policy gets it right. Sometimes it gets it wrong

and sometimes it is surprised

(Note: This letter/post is longer than usual, but I hope the argument is easy to follow)

The first order of business is to define what is meant by “monetary policy”, particularly how can we gauge the stance of monetary policy.

Recently Scott Sumner of the Mercatus Center wrote a paper titled “A Critique of Interest Rate-Oriented Monetary Economics.” 1

Interest rates have played a central role in monetary policy analysis. The short-term nominal interest rate is often viewed as the appropriate instrument of monetary policy, and interest rates are also viewed as an indicator of changes in the stance of money policy. In this paper, I show that too much weight is placed on movements in interest rates as a policy indicator and that confusion on this point has contributed to previous monetary policy failures. More speculatively, one needs to rethink whether interest rates are even the appropriate policy instrument for central banks.

What I find surprising is that “interest rate-oriented monetary economics” still “rules the waves".”

Fifty years ago, Milton Friedman wrote “A Monetary Theory of Nominal Income”. Where we read:

In particular, the approach provides an interpretation of the empirical generalization that high interest rates mean that money has been easy, in the sense of increasing rapidly, and low interest rates, that money has been tight, in the sense of increasing slowly, rather than the reverse.

More recently Bernanke himself put it very clearly in On the legacy of Milton and Rose Friedman´s Free to Choose (2003):

As emphasized by Friedman (in his eleventh proposition) and by Allan Meltzer, nominal interest rates are not good indicators of the stance of policy, as a high nominal interest rate can indicate either monetary tightness or ease, depending on the state of inflation expectations. Indeed, confusing low nominal interest rates with monetary ease was the source of major problems in the 1930s, and it has perhaps been a problem in Japan in recent years as well.

Five years later in his farewell speech during his last FOMC Meeting, Fed Governor Mishkin said:

What I’d like to spend some time on—because I feel this is sort of my swan song, but maybe because I’m a classy guy, I’ll call this my “valedictory remarks”—are three concerns that I have for this Committee going forward. I’m not going to be able to participate, but I have a chance now to lay them out.

The first is the real danger of focusing too much on the federal funds rate as reflecting the stance of monetary policy. This is very dangerous. I want to talk about that.

If not interest rates, what defines the stance of monetary policy?

In the same event in 2003 linked above, Bernanke says:

The imperfect reliability of money growth as an indicator of monetary policy is unfortunate, because we don’t really have anything satisfactory to replace it. As emphasized by Friedman . . . nominal interest rates are not good indicators of the stance of policy . . . The real short-term interest rate . . . is also imperfect . . . Ultimately, it appears, one can check to see if an economy has a stable monetary background only by looking at macroeconomic indicators such as nominal GDP growth and inflation.

I downplay inflation as an indicator of the stance of monetary policy. It can be misleading when supply shocks (oil prices, productivity) are involved. I´ll show later that Bernanke´s close focus on inflation, for example, was a major factor behind the onset of the Great Recession in 2008. That leaves nominal GDP (NGDP) growth.

That is, however, still an incomplete indicator. I´ll show that an economy might “enjoy” nominal stability (stable NGDP growth) even while remaining in a “depressed state”. So the level trend path along which the economy “enjoys” nominal stability is important in assessing the stance of monetary policy.

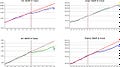

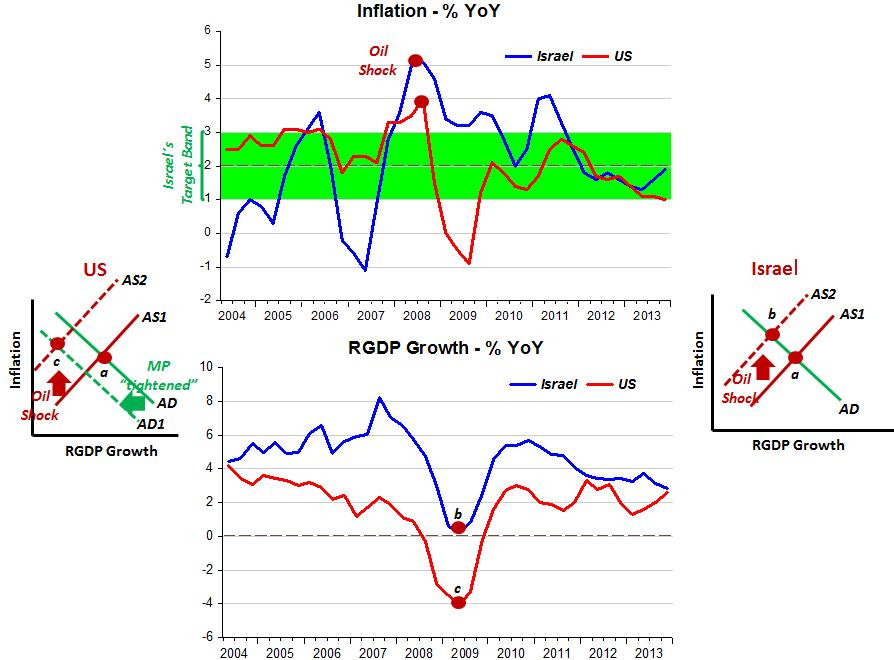

The charts below provide examples of monetary policy “getting it wrong” and “getting it right” at the time of the Great Recession (2008-09). The US and Eurozone (EZ) “got it wrong” because nominal stability was forsaken, with NGDP growth tumbling below the trend level path. Meanwhile, Israel and Poland “got it right”, with NGDP remaining very close to the trend level path. (Poland “let the ball drop” a few years later).

Now, the question is how did the Fed and the ECB get it wrong? To grasp that, I write the equation of exchange in growth form:

Where g(x) refers to the growth rate of M=money supply, V=Velocity, P=Prices and Y=real GDP

The equation of exchange is an identity, so to give it economic meaning we say that to keep NGDP growth on a stable path (or maintain nominal stability), the Central Bank must “calibrate” the growth of M (under its close control) to adequately offset the growth in V, where the word “adequately” means “so as to keep growth in NGDP at the ongoing stable trend level.”

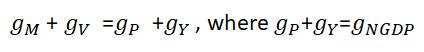

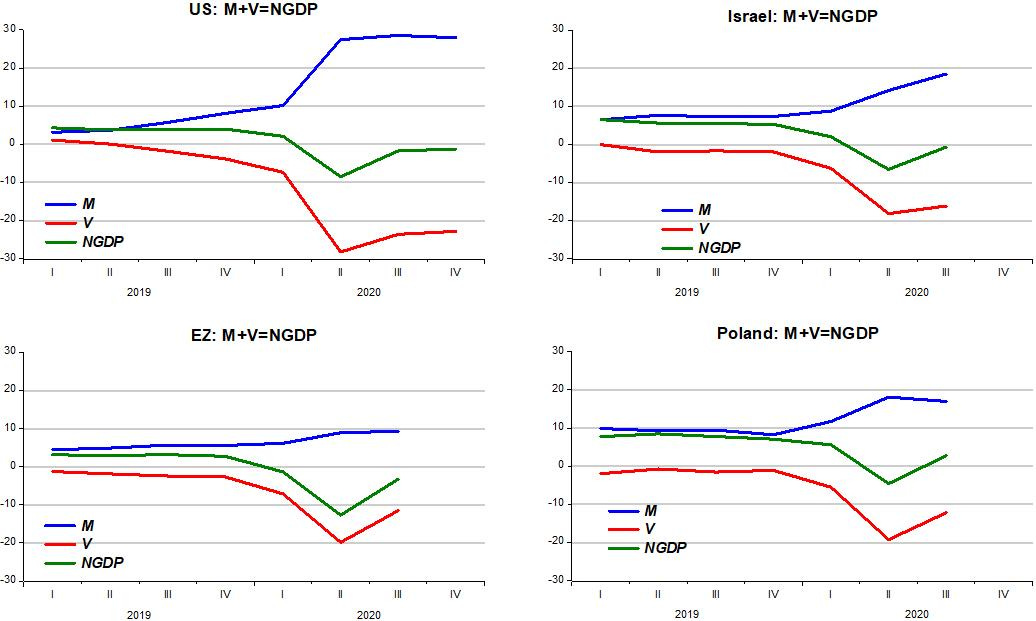

It is clear from the charts above that while Israel and Poland managed to closely offset a fall in velocity (rise in money demand) due to increased uncertainty related to the budding financial crisis, the US and Eurozone did not.

The next panel of charts makes this clear.

We´ve seen in the first panel above, that Israel pursued throughout a monetary policy conducive to provide nominal stability. There´s irony here, because apparently it was mostly luck!

From 2005 to 2013, Stanley Fisher (who later became Vice Chair of the Fed) was President of the Bank of Israel (BoI). It is notable that in 1995 he published in the American Economic Review “Central Bank Independence Revisited”:

In the short run, monetary policy affects both output and inflation, and monetary policy is conducted in the short run–albeit with long-run targets and consequences in mind.

Nominal- income-targeting provides an automatic answer to the question of how to combine real income and inflation targets, namely, they should be traded off one-for-one…Because a supply shock leads to higher prices and lower output, monetary policy would tend to tighten less in response to an adverse supply shock under nominal-income-targeting than it would under inflation-targeting.

Fast forward: In a speech in April 2013, just before stepping down from Governor of the Bank of Israel, Fischer said:

There are those who support setting a nominal GDP target. I think that this is very impractical. The data that we receive on nominal GDP are very unstable. There are changes of whole percentage points between the various estimates of GDP. For this reason, I think that there is no reason to use nominal GDP as a target.

Ironically, as Governor of the Bank of Israel from 2005 to 2013, Stanley Fischer (managed) to keep NGDP growing at a stable rate along a level path!

As he wrote in 1995: “Because a supply shock leads to higher prices and lower output, monetary policy would tend to tighten less in response to an adverse supply shock under nominal-income-targeting than it would under inflation-targeting. Thus nominal-income-targeting tends to imply a better automatic response of monetary policy to supply shocks”.

And that perfectly explains the difference between what happened in Israel and what came about in the US as the charts below indicate. While in the US the rise in oil prices led the Fed, (for fear of inflation) to “tighten” (constrain aggregate nominal spending (NGDP or Aggregate Demand (AD)), in Israel NGDP remained “on trend”. The result was a deep recession in the US while Israel experienced only a real growth slowdown.

Concentrating on just the US and the Eurozone (EZ) on the first panel above, we notice that after the Great Recession (GR), the US entered a period of nominal stability that lasted until 2019, albeit at a lower trend level path. That means the initial monetary policy mistake was not reversed, with the Fed content in keeping the economy in “depressed stability”.

For the EZ, things are worse. After the GR, The ECB also kept the economy at a lower level trend path, but this did not last long, because in 2011, French ECB President Trichet, who wanted to show that he was more hawkish on inflation than the Germans, tightened policy further (mostly because of oil price increases after the GR ended). So the NGDP level was decreased further, before embarking on a “super depressed” stable path to 2019.

Now, if you look at the end of the sample in the charts in the first panel, you see that, contrary to what is observed during the GR, the pattern of NGDP is the same in all countries. That´s why I subtitled this post as “and sometimes it is surprised”.

That “surprise” came from the Covid19 shock, something different from “policy mistakes”. All the countries indicate that monetary policy was successfully achieving nominal stability, even though, with the exception of Israel, at a “depressed” level path. Then the Covid19 surprise happened.

The charts illustrate (only the US had 2020 Q4 data available)

Poland and Israel showed a quicker and more forceful response of monetary policy, with NGDP growth falling the least. The ECB had the worst performance, with an only timid monetary response to the fall in velocity, which was not different from the drop observed elsewhere.

The US experienced the biggest fall in velocity, which explains the higher rate of money growth (all charts have the same scale to make comparison easier).

Traditional monetarists look at that, and reason that inflation will move up significantly and soon. That reasoning follows from assuming, in the equation of exchange, that velocity is stable, so the equation of exchange can be written as (in growth form):

M-Y=P meaning that inflation (P) will rise if money growth (M) increases faster than growth in real output (Y).

But velocity is not stable and fell by a lot, so it´s useless to reason as if velocity were stable!

The Fed is “afraid”, so NGDP growth has stabilized at slightly negative value and Powell has declared being “all for fiscal stimulus”.

Krugman has just published “Nonstimulus Arithmetic”:

Back in January 2009 I posted an entry to my blog titled “Stimulus arithmetic” that worked through the math of the looming output gap and what we knew about the Obama stimulus. I warned that the stimulus was drastically underpowered, and issued a dire political warning that unfortunately came true

The Covid19 shock does not require “fiscal stimulus”, but rather “fiscal relief”, and the only “stimulus” that matters is of the monetary variety because, otherwise, the economy will be trapped in an even more depressed stability!

Eleven years ago I argued that to insist on targeting the Fed funds rate could be harmful.