Price surges, distributional conflicts & getting comfortable in football stadiums

The Fed should learn to do Monetary Policy!

From what I can tell, our models seem ill-equipped to handle a fundamentally different source of inflation, specifically, in this case, surge pricing inflation.

Olivier Blanchard @ojblanchard1

1/8. A point which is often lost in discussions of inflation and central bank policy. Inflation is fundamentally the outcome of the distributional conflict, between firms, workers, and taxpayers. It stops only when the various players are forced to accept the outcome.

Nordhaus compared inflation to what happens in a football stadium when the action on the field is especially exciting. (If you don’t find American football exciting, think of it as a soccer match.) Everyone stands up to get a better view, but this is collectively self-defeating — your view doesn’t improve because the people in front of you are also standing, and you’re less comfortable besides.

People forget that inflation is a monetary phenomenon! By “forgetting” that basic principle, views/theories of inflation just keep “looping”. For example, during the high and rising inflation of the 1980s and early 1990s in Brazil, it was common to ascribe inflation to “distributional conflicts”. The government tried price controls (PC), incomes policy and even the sequestration of peoples financial assets, all to no avail. Until one day, someone cried “BOO” and inflation “disappeared”! (the “BOO” was a change in the monetary policy regime). Also, real growth was significantly positive in 1994 and 1995 (4%+) and unemployment fell! (For a short but neat counterargument to Blanchard´s DC view on inflation, see “Is inflation a distributional phenomenon?)

In fact, inflation happens when the conduct of monetary policy is not appropriate. What does “appropriate” mean in this context? It means that monetary policy is being conducted so as to maintain Nominal Stability. By nominal stability it is meant that aggregate nominal spending (or NGDP) growth evolves along a stable level growth path.

How does the Central Bank achieves nominal stability? The best analogy here is with the workings of a “thermostat” . Just as the inside temperature of a house will remain stable when the thermostat successfully offsets changes in the outside temperature, the Central Bank will obtain nominal stability if it acts to change the supply of money so as to offset changes in velocity (the inverse of money demand), the “outside temperature”.

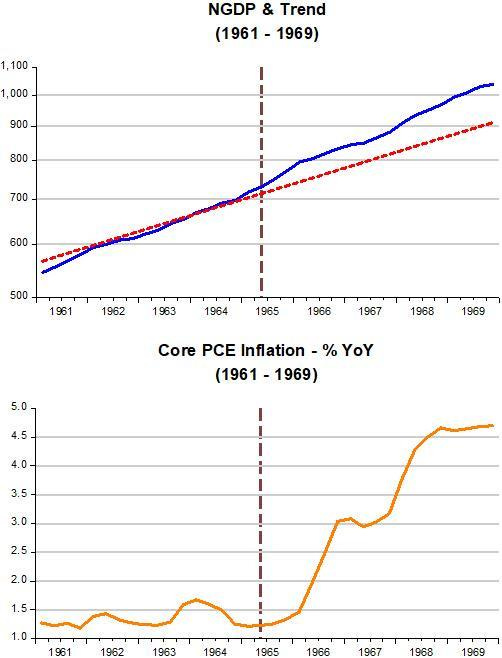

This was true for the 20 years (Great Moderation) between 1987 and 2007 and again from 2010 to 2019 (the “Depressed Moderation). See here.

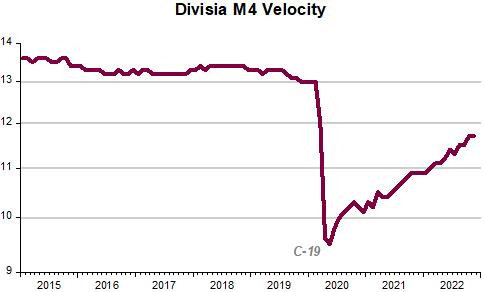

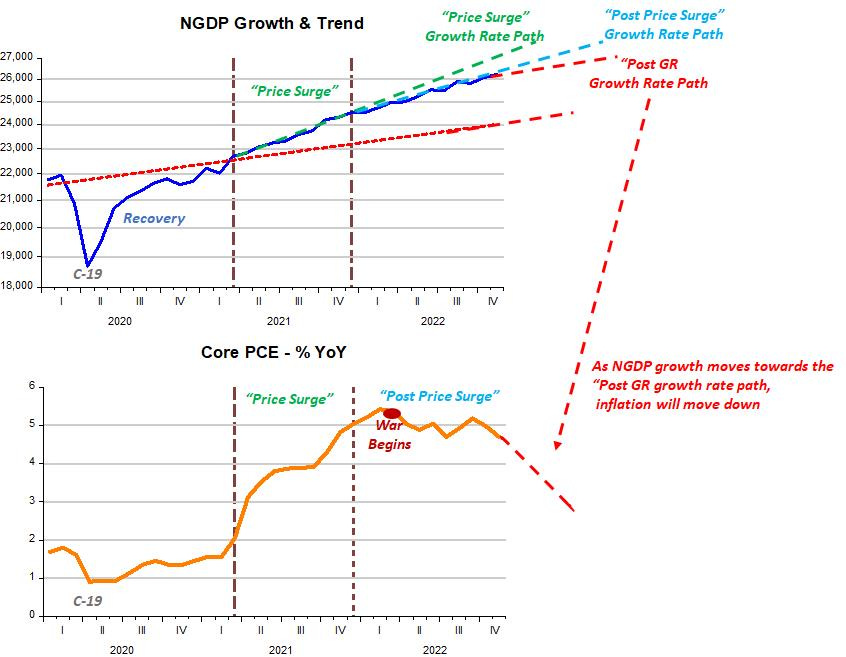

The charts below illustrate the nominal economy (NGDP & Core PCE inflation) since January 2020 when the C-19 shock happened. The first thing to note is that C-19 induced a massive velocity shock (which was initially much stronger than the other C-19 associated shocks, like lockdowns and supply chain disruptions).

The money supply was raised quickly, but not quickly enough to offset the big drop in velocity. NGDP fell, but quickly began to recover. Kashkari´s “Price Surge” begins when NGDP climbs above the trend growth path it was on since the end of the Great Recession1. A “post price surge” follows the reduced growth rate trend of NGDP. Interestingly, peak core PCE inflation coincides with the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Maybe inflation would have dropped more if it weren´t for that shock…

If velocity keeps moving towards its pre C-19 shock at the ongoing rate of close to 7% YoY, for NGDP growth to drop to the 4% post Great Recession growth rate, money supply growth will have to “grow” at negative 3% (at present Divisia M4 growth is close to 0%) until Velocity flattens out. With the NGDP growth path falling towards 4%, core PCE will continue to fall.

Note that to get inflation down close to the 2% target level, it is NOT necessary for NGDP to be brought down to the LEVEL that prevailed post Great Recession (just as inflation came down with the Volcker adjustment without having to bring the LEVEL of spending down to the level that prevailed before the Great Inflation). If that “gimmick” were tried, brace for a second Great Depression!

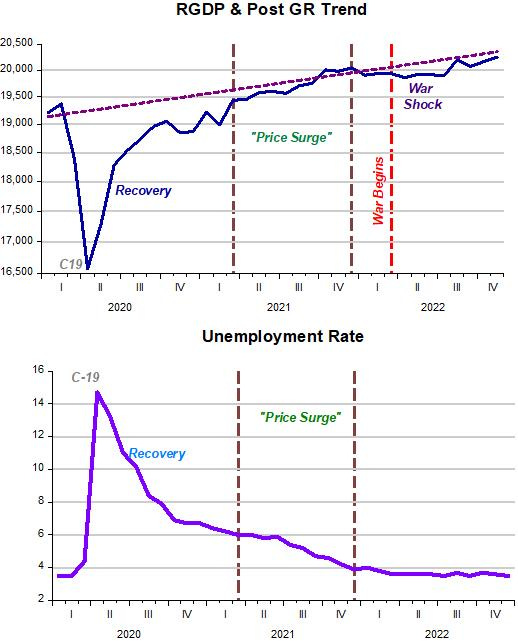

Now I look at the real economy. Real output (RGDP) and unemployment. The charts illustrate.

The interesting thing is to observe what happens to RGDP during the “price surge” or, more precisely when NGDP climbs above the post GR trend. At that point, supply was constrained by the effects of C-19. It appears that with the Fed “pumping” nominal aggregate spending, it helped brake the “supply barriers”, with RGDP climbing back to trend and unemployment falling further.

This is consistent with the argument recently developed by Brad Delong in “When Will Interest Rates Stop Rising? Now Would Be Good”:

The inflation we have had over the past two years has been, largely, a good thing—or, rather, a necessary consequence of a very good thing. Not to have had an inflation surge as we reopened the economy after the plague—that would have been to run unacceptably high risks of a repeat of the disastrously slow recovery of the Obama years. Moreover, we needed wage inflation in the goods-producing, logistics, and information sectors in order to pull workers returning to work into the sectors that needed to expand to get the economy to full employment given the altered post-plague shape of demand. And we needed inflation at the bottleneck breaks in supply chains to incentivize their repair.

The only change I would make is instead of using the word “inflation”, I prefer saying “the increase in NGDP has been a good thing”.

The “war shock” pulled real output down, leading to the cries of “we´re in a recession”. RGDP, however, is back close to the post GR trend level path.

What all that was said implies is that if the Fed “thinks clearly”, a “soft landing” is in the cards, with inflation coming down, real output growing and unemployment remaining low. If this is perceived to be a likely outcome, the markets will react accordingly.

re: "People forget that inflation is a monetary phenomenon!"

And velocity (demand for money), is sometimes neglected in the "equation of exchange"

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/data/PMSAVE.txt

Personal savings, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Release: Personal Income and Outlays fell from 2021-03-01 $5732.7 to 2022-11-01 $461.2

How much dis-savings is left?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PSAVERT

Secular stagnation, chronically deficient aggregate demand, was also predicted in 1980. Professor emeritus Leland James Pritchard (Ph.D., Chicago Economics 1933, M.S. Statistics) never minced his words, and in May 1980 pontificated that:

“The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act will have a pronounced effect in reducing money velocity”.

The "Great Moderation" simply was the result of an increasing volume and proportion of time deposits relative to transactions deposits in the commercial banking system. It also reflected an increase in FDIC insurance levels.