Debating monetary policy

Rules? Discretion? Rules for instruments or for targets?

I thought the title to this recent post was on the dot: “Well, which is it, young feller? Will you tighten policy if inflation gets too high or will you wait for full employment?”

There is not a rule binding monetary policy behind this view. It´s all dependent on the Fed´s (maybe constrained) discretion. But wait, the Fed just reintroduced a discussion of monetary policy rules in its latest Monetary Policy Report, released February 19.

A new rule is introduced to capture the new policy framework based on shortfalls from maximum employment. What gets emphasized, however, are the “limitations of simple policy rules”.

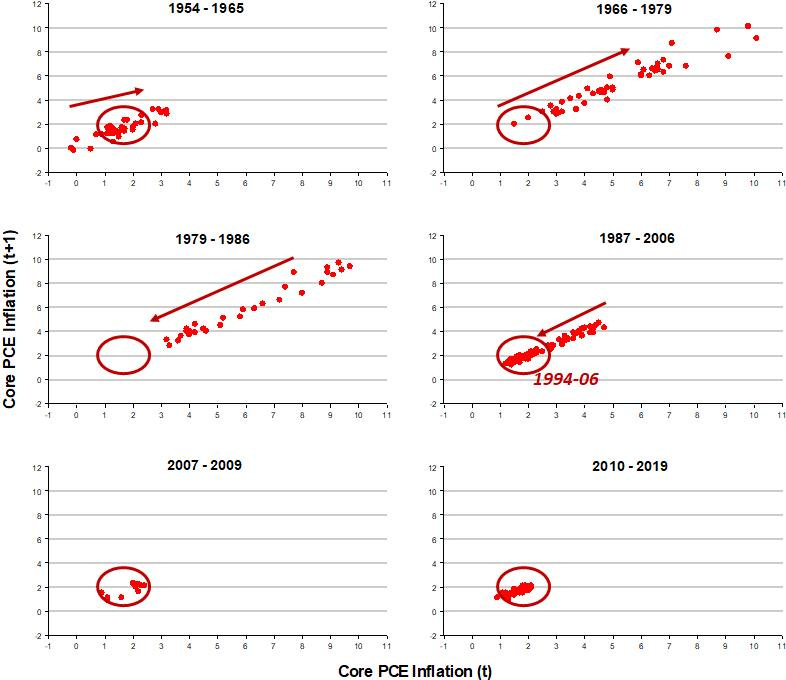

All the simple rules for the policy instrument, regarded as being the fed funds rate (FF), are variants of the original Taylor-rule, which relates the setting of the policy instrument as a function of variables such as the deviation of inflation from its target rate, the output (or employment) gap and a measure of the “neutral, natural, or equilibrium” interest rate.

Six years ago (2015), Bernanke “debated” Taylor´s advocacy for his rule in “The Taylor Rule: A benchmark for monetary policy?”:

The Taylor rule is a valuable descriptive device. However, John has argued that his rule should prescribe as well as describe—that is, he believes that it (or a similar rule) should be a benchmark for monetary policy.

Starting from that premise, John has been quite critical of the Fed’s policies of the past dozen years or so. He repeated some of his criticisms at a recent IMF conference in which we both participated. In short, John believes that the Fed has not followed the prescriptions of the Taylor rule sufficiently closely, and that this supposed failure has led to very poor policy outcomes. In this post I will explain why I disagree with a number of John’s claims.

And concludes:

I’ve shown that US monetary policy since the early 1990s is pretty well described by a modified Taylor rule. Does that mean that the Fed should dispense with its elaborate deliberations and simply follow that rule in the future? In particular, would it make sense, as Taylor proposes, for the FOMC to state in advance its rule for changing interest rates?

No. Monetary policy should be systematic, not automatic. The simplicity of the Taylor rule disguises the complexity of the underlying judgments that FOMC members must continually make if they are to make good policy decisions.

Almost simultaneously with Bernanke´s “debate” with Taylor, Athanasios Orphanides wrote “Fear of Liftoff: Uncertainty, Rules, and Discretion in Monetary Policy Normalization”:

The Federal Reserve’s muddled mandate to attain simultaneously the incompatible goals of maximum employment and price stability invites short-term-oriented discretionary policymaking inconsistent with the systematic approach needed for monetary policy to contribute best to the economy over time.

The discussions above pertain to the period since the onset of the Great Recession, a period during which the Fed Funds remained near zero for much of the time and monetary policy became “discredited”.

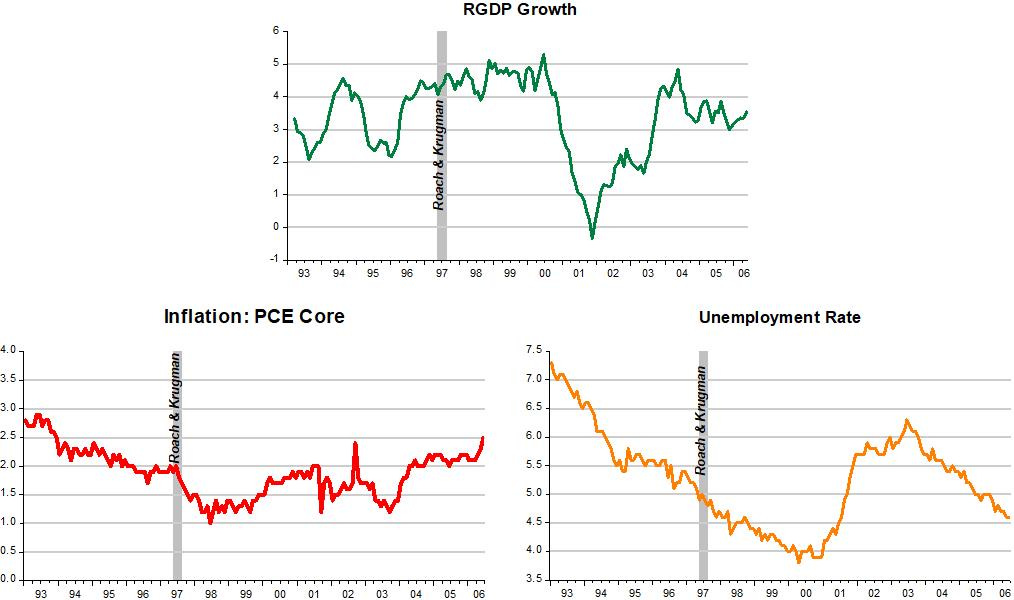

Even if we go back almost a quarter century, when in 1997 the economy was smack in the middle of the Great Moderation, a period during which monetary policy was “lauded”, many had doubts about the settings for the monetary policy instrument, the FF rate.

After having spent one year with the FF rate at 5.25%, in March of 1997 the Fed increased the FF rate by 25 basis points. Many thought the Fed was “mistaken”.

Steven Roach, at the time Chief-Economist for Morgan Stanley wrote in May:

(…) And so we come full circle. The speed limit is far less important than the output gap in assessing both inflation risk and the policy response required to counter that risk. Like it or not, the US economy has crashed through its inflation stable growth…A sustained downshift in the economy – with real GDP growth slowing to at least 1.5% for a year – is the only way out. And I stand by my view that it´s going to take considerably higher interest rates to produce that result.

Paul Krugman wrote in July: “HOW FAST CAN THE U.S. ECONOMY GROW?”

Most economists believe that the US economy is currently very close to, if not actually above, its maximum sustainable level of employment and capacity utilization.

So standard economic analysis suggests that we cannot look forward to growth at a rate of much more than 2 percent over the next few years. And if we - or more precisely the Federal Reserve - try to force faster growth by keeping interest rates low, the main result will merely be a return to the bad old days of serious inflation.

As the charts indicate, not one of those “predictions” came about; and four years later the economy faltered after the Fed followed their “recommendations”.

It appears, therefore, that instrument rules are not very “appealing”. Long ago, Milton Friedman had proposed an instrument rule for the money supply, where the money supply would grow at a constant rate. But that was discarded for being “inoperable”.

Not long after the Great recession ended, the IMF hosted an international conference on Macro and Growth Policies in the Wake of the Crisis. The IMF´s Chief-Economist at the time was Olivier Blanchard, who presented a “Guide to the Conversation”.

Blanchard summarizes the framework and then puts forth some ideas for discussion. I´ll only highlight the first point of the framework and the first point of the ideas for discussion.

According to Blanchard the first point in the “framework” is summarized by the following:

The essential goal of monetary policy was low and stable inflation. The best way to achieve it was to follow an interest rate rule. If designed right, the rule was not only credible, but delivered stable inflation and ensured that output was as close as it could be to its potential.

Then, from the early 1980s on, macroeconomic fluctuations were increasingly muted, and the period became known as the “Great Moderation”. Then the crisis came. If nothing else, it forces us to do a wholesale reexamination of those principles. Here are some ideas to guide the conversation: The first of which is:

Economic imbalances: Achieving stable inflation is good, but we can now see it does not guarantee stable output. Before the crisis, steady output growth and stable inflation hid growing imbalances in the composition of output and in the balance sheets of households, firms, and financial institutions, as well as growing misalignments of asset prices. These imbalances ended up being very costly. The question now is how best to address such imbalances.

Should we think of macroeconomic policy as having three legs—monetary, fiscal, and financial—each with separate authorities? Or should we think of extending both the mandate and the set of tools of monetary policy to cover both output and financial stability? And, if so, what tools do we have and how do we use them?

To begin with, the goal – low and stable inflation – is not well defined. There are several “inflations” and they can be very different. The “interest rate rule” is also problematic because it cannot fall below zero. In addition, as argued by central bankers like Bernanke and Mishkin, and confirmed by Friedman, the policy rate is a poor indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

As Blanchard notes in the first point of his “guide to the conversation”, low and stable inflation does not guarantee stable output. So how come that for about 20 years the economy experienced falling and than stable inflation and stable output?

It must be that, in practice, something else was happening, and that when this “something else” went away all “hell broke loose”. This conjecture also indicates that stability in output and inflation was not “hiding” growing imbalances.

Imbalances are always present in a dynamic economy. They are often the result of wrong incentives. It is not the case that macro “stability” fosters, or hides, imbalances, but that sudden instability make them worse and more difficult to redress.

In the 1990s, Friedman, a fierce critic of the Fed´s performance over the previous decades, acknowledged that since the mid-1980s, the monetary authorities had been successful in stabilizing the economy.

In 2003, Friedman gave the simplest explanation for the “Great Moderation” with his “Thermostat Analogy”.

In essence, the new found stability was the result of the Fed (and many other Central Banks) stabilizing nominal expenditures. In that case, from the quantity equation of money, according to which MV=PY, the Fed managed to offset changes in V with changes in M, keeping nominal expenditures, PY, reasonably stable. Note that PY or its growth rate (p+y), contemplates both inflation and real output growth, so that stabilizing nominal expenditures along a level growth path means stabilizing both inflation and output growth.

That is an example of a target rule, where the target is a “stable nominal expenditure (NGDP) growth”.

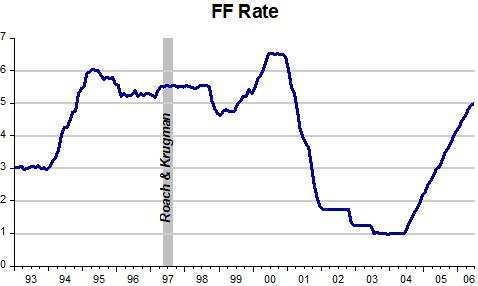

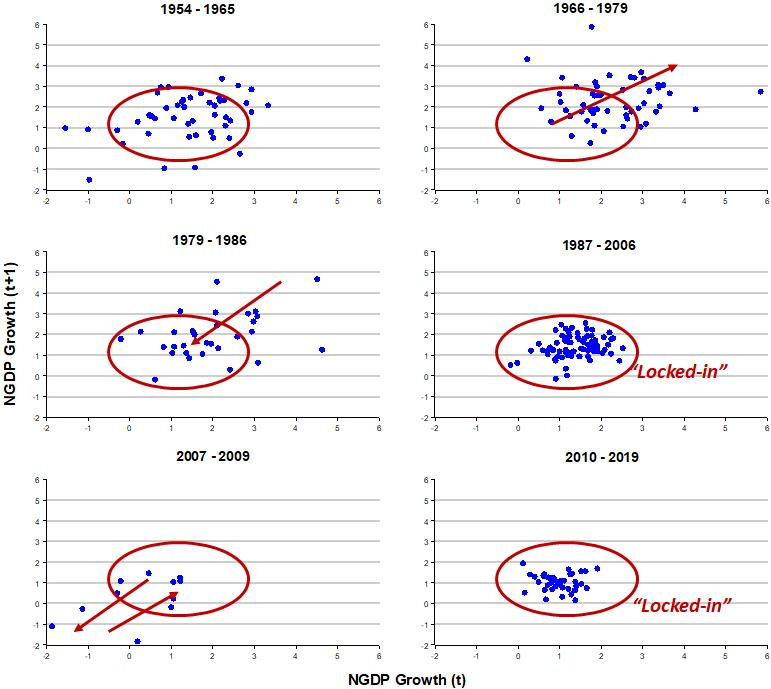

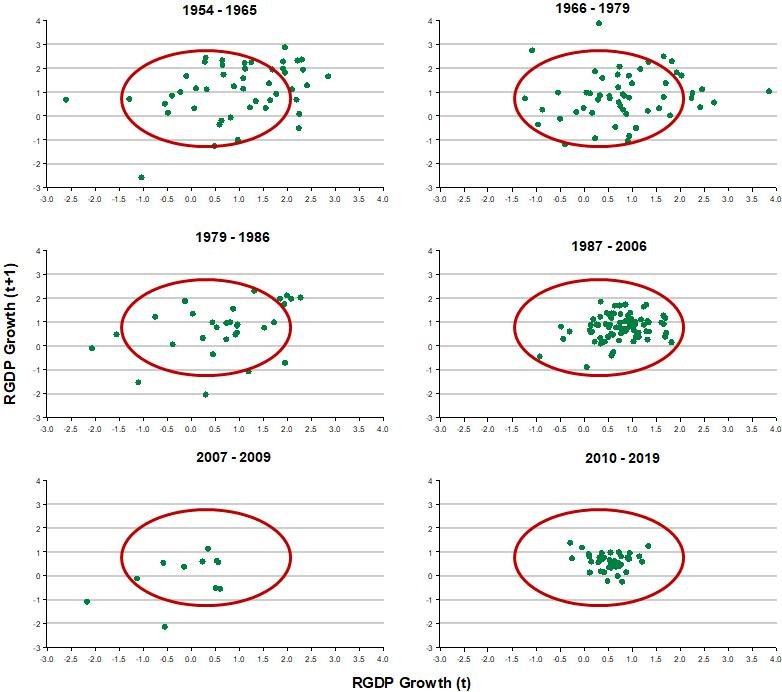

The panels below consider different periods since 1954. Note that during the Great Moderation (1987 - 2006), a stable growth rate of NGDP is associated with stable inflation and stable real growth. That is also the case following the upheaval of the Great Recession.

But the last 11 years don´t bring forth “good feelings”. This period has been alternatively called “New Normal”, “Secular Stagnation”, “Lesser Depression”, among others, and none flattering.

This naturally leads us to modify the target rule. Instead of just “Stable NGDP Growth”, we add “Level Target” (NGDP-LT), because it appears that the level path along which NGDP growth is stable is important to “enhance good feelings” about the economy.

The charts are presented in a way to make easy the comparison of (in)stability that prevailed over the different periods. So, we compare growth rates at t and t+1. The more “bunched together” the rates are, the more stable the process is. The “circle of stability” makes the comparison easier.

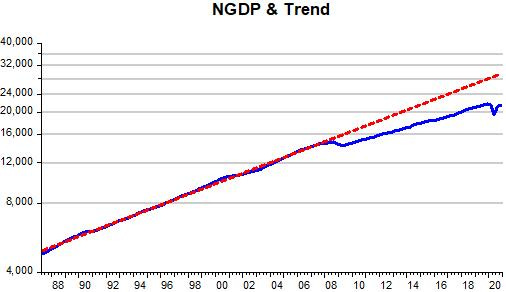

To bring attention to the level path along which NGDP evolves, the next chart shows how closely NGDP remained to the Great Moderation Trend Path. Note that in 2008, it “stepped down” into a lower level path. NGDP then evolved stably along this lower trend path.

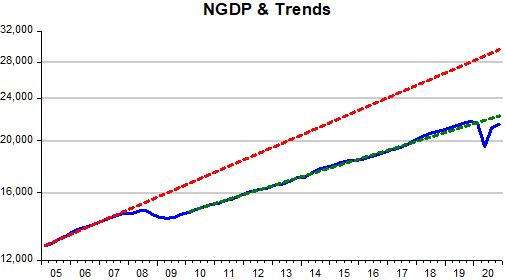

The next chart is just a zoom-in on the previous chart and indicates the new stable path along which nominal spending progressed since 2010, before being “knocked-down” by the Covid19 pandemic.

The outcomes depicted in the two charts above constitute, at least to me, living proof that the Fed can devise an effective rule to keep nominal expenditures growing at a stable rate at a particular level (the target). The rule in this case is not the “juggling” of an interest rate but “offsetting changes in velocity with changes in money supply” so as to keep NGDP on a stable growth path.

The Fed since 1987 has essentially done that, managing to stabilize NGDP at two different growth rates along two different level paths. The target could certainly be improved by changing it to “stabilize NGDP-LT”.

Looking at what happened in 2008, if the Fed had an NGDP-LT target it would not only have tried to bring spending back to the trend path but, more importantly, it would not have allowed NGDP to drop in the first place. But the Fed had an implicit (at that time) inflation target (of around 2%). The oil shock temporarily increased headline inflation and the Fed got very scared! By strongly constraining spending (NGDP fell in absolute terms), the Fed was a source of massive instability1.

And so we reach 2020 and the Covid19 shock. This was a different “animal” from the usual demand or supply shocks economists deal with, carrying elements of both. From the outcome, however, with both inflation and real output growth falling, the demand shock element overwhelmed the supply shock element.

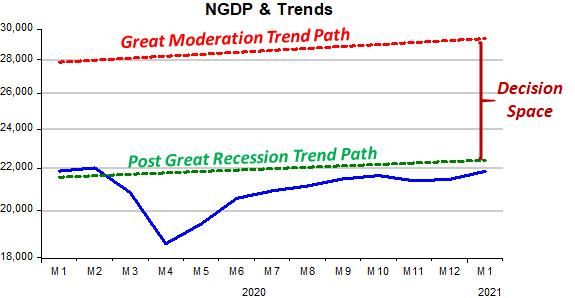

The chart illustrates, showing where spending is both relative to the post GR trend level path and relative to the GM trend level path.

The Fed now has to “choose” where it wants to take aggregate spending to. Just back to the post GR trend level path (aka “new normal”, “secular stagnation”, etc.), or to somewhere inside the “decision space”.

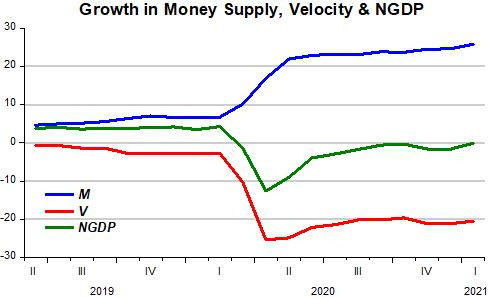

That has implications for how the Fed will implement the target rule, meaning how it will change the money supply to offset velocity changes. The chart below illustrates.

Given the nature of the Covid19 shock, it is quite likely that once the pandemic falls below some critical level, the demand for money will fall (velocity rises). Just as the Fed was quick to begin offsetting the sudden big drop in velocity when the pandemic hit, it can work in the other direction, especially since velocity changes are likely to be more gradual.

One problem is that the Fed prefers to speak the language of inflation and unemployment. That gives rise to “tongue in cheek” comments on twitter;

Maybe this is what it takes to bring about a regime change to 'make-up' policy in a relatively orderly fashion. No shortcuts, just hard work by the Fed to stay the course.

Quote Tweet

Victoria Guida

Fed: We want more inflation

Markets: But then there might be more inflation

Fed: Yes

Markets: So you’ll be raising rates soon?

Fed: No, we want more inflation

Markets: But then there might be more inflation.

Fed: Yes

Markets: You’ll be raising rates soon.

It is ironic to see that if the Fed spoke the language of NGDP (level and rates), it would more “peacefully” reach its goals (in the sense of being able to keep inflation low & stable and see unemployment falling to its (encompassing) full employment level). In other words, contrary to what Orphanides (and other thousands) believes, there´s no incompatibility in trying to simultaneously attain the goals of maximum employment and price stability.

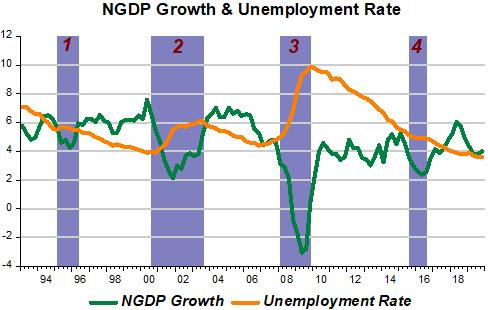

The next chart shows that keeping NGDP growth on a stable path leads to a continuous fall in the unemployment rate. The level along which spending growth evolves determines the overall “quality” (employment ratios, participation rates of all segments, among others) of the labor market.

Note, in particular, how sensitive unemployment is to fluctuations in NGDP. Small fluctuations (1,4) will only stop the fall in the unemployment rate. A large fall in NGDP growth will have a significant effect (2), while a massive drop will have “catastrophic” effects (3).

PS March 18 This announcement was just out. Wonder what the “magic” will be!

Naturally, the Fed plays down its responsibility and the GR was the outcome of the house bust, inadequate regulation and such. To get a better view, it is worth reading Housing Policy, Monetary Policy, and the Great Recession.

Spencer, I completely fail to understand your comments!

Really, all the problems are captured in the Keynesian macro-economic persuasion that maintains a commercial bank is a financial intermediary (sic).