The Accommodation Trap

Why Long-Term Rates Would Rise Under a Subservient Fed Chair

Introduction

The financial markets’ initial response to reports that Kevin Hassett would be nominated as Federal Reserve chair appeared to validate the Trump administration’s strategy.

Hassett himself gently pushed back on Bloomberg’s reporting in an interview with Face the Nation on Nov 30:

I am not sure that Bloomberg has the story right,” before adding that he was “honored” to be among those under consideration.

But Hassett acknowledged that financial markets had a “very, very positive” response to the reporting, noting a drop in Treasury yields that reflected expectations of lower interest rates in the months ahead.

“I think that the American people could expect President Trump to pick somebody who’s going to help them have cheaper car loans and easier access to mortgages at lower rates — and that’s what we saw in the market response to the rumor about me,” Hassett said.

Treasury yields fell, seemingly confirming that a more accommodative Fed leadership would deliver the lower borrowing costs the White House seeks.

But this optimistic interpretation fundamentally misunderstands how long-term interest rates are determined.

While Hassett’s appointment might allow the Fed to cut short-term policy rates more aggressively, the very factors that would enable such cuts—his unprecedented closeness to the sitting president and perceived willingness to subordinate monetary policy to political demands—would likely trigger a significant increase in long-term rates.

The initial market rally may prove to be precisely wrong: appointing a Trump loyalist to chair the Federal Reserve would almost certainly raise, not lower, the borrowing costs that matter most for American households and businesses.

Long-term interest rates reflect market expectations about many factors over extended time horizons, but inflation expectations stand paramount among them. Investors who commit capital for ten or thirty years demand compensation for expected inflation over that entire period.

This is why credible central bank independence is so valuable: it anchors long-term inflation expectations, allowing long-term rates to remain relatively low even when short-term rates fluctuate.

The Federal Reserve’s hard-won credibility rests on decades of demonstrated independence from political pressure. While presidents appoint Fed chairs, once appointed, chairs have consistently prioritized their statutory mandate for price stability over White House preferences.

Paul Volcker raised rates dramatically in the early 1980s despite intense political opposition. Alan Greenspan resisted pressure from both parties. Even Jerome Powell, a Trump appointee, has maintained independence despite the former president’s public attacks and demands for rate cuts.

This independence creates what economists call an “independence premium”—the reduction in long-term rates that results from credible inflation-fighting commitments.

When markets believe the central bank will subordinate all other considerations to price stability, they price in lower inflation over time, reducing the compensation demanded in long-term yields.

Conversely, when central bank independence appears compromised, this premium evaporates and long-term rates rise to reflect higher inflation expectations and greater uncertainty about future monetary policy.

Hassett’s Unprecedented Presidential Ties

Kevin Hassett’s relationship with President Trump differs fundamentally from any modern Fed chair’s relationship with the appointing president.

He currently serves on White House staff, giving him daily proximity to Trump. He has been a consistent defender of Trump’s economic policies, including tariffs that most economists view as inflationary.

Most tellingly, Trump himself described the nomination as selecting “somebody who’s going to help” deliver lower rates—framing monetary policy explicitly as a tool for achieving administration goals rather than as an independent institution pursuing statutory mandates.

The betting markets’ 80% probability that Hassett will be nominated reflects precisely this expected subordination of Fed independence to White House preferences.

Investors are wagering that Trump will get the malleable Fed chair he has long demanded. But this same calculation—that Hassett would run monetary policy according to Trump’s wishes—is exactly why his appointment would undermine the Fed’s credibility and push long-term rates higher.

Historical precedent strongly supports this concern. Every instance where central banks have lost independence and succumbed to political pressure for easier money has resulted in rising long-term rates, not falling ones.

The mechanism is straightforward: markets recognize that politicized monetary policy leads to higher inflation, and they demand higher yields to compensate.

The 1970s American Experience

The United States has direct experience with the consequences of politically-influenced monetary policy.

During the 1970s, Federal Reserve chairs William McChesney Martin, Arthur Burns, and G. William Miller faced intense political pressure to keep rates low and accommodate fiscal expansion. Burns, in particular, coordinated closely with the Nixon administration and proved reluctant to tighten policy despite rising inflation.

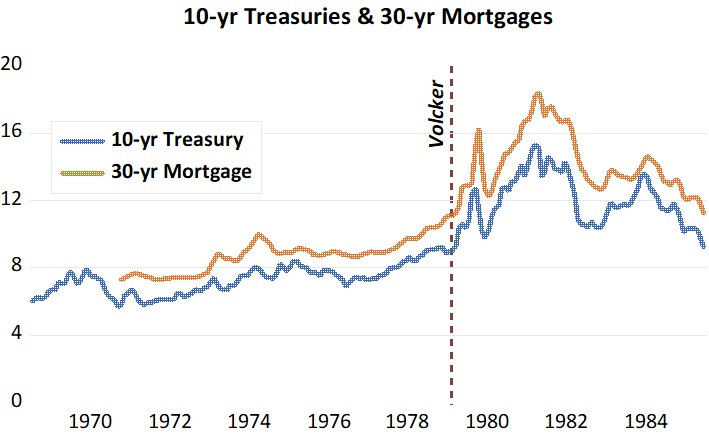

The result was not lower borrowing costs but a disaster for long-term rates. As inflation expectations became unanchored, long-term Treasury yields soared from around 6% in the late 1960s to 15% by late 1981. 30-year mortgage rates exceeded 18%.

The economy suffered through multiple recessions as the Fed alternated between accommodation and insufficient tightening, never committing credibly to price stability.

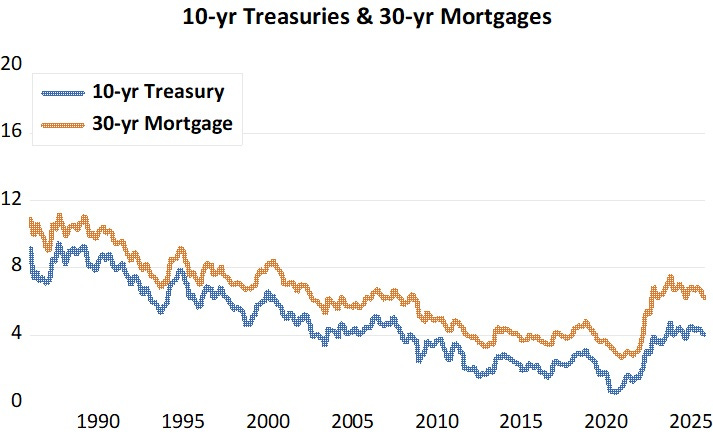

Only when Paul Volcker decisively broke this pattern—raising rates to punishing levels and explicitly rejecting political pressure—did long-term rates begin their decades-long decline.

Volcker’s willingness to endure recession and political attacks to restore price stability rebuilt the Fed’s credibility. This credibility, maintained by his successors, is the foundation for the falling long-term rates America has enjoyed since the mid-1980s.

Appointing Hassett would represent a return to the 1970s model: a Fed chair selected explicitly for willingness to accommodate political demands for lower rates. Markets understand this history and would price accordingly.

International Examples: Turkey and Argentina

Recent international experience provides even starker warnings. Turkey under President Erdoğan offers a particularly instructive case study. Erdoğan has long promoted the unorthodox view that high interest rates cause inflation rather than cure it. He has systematically replaced Turkish central bank governors who resisted his demands for rate cuts, cycling through four governors between 2019 and 2023.

The result has been catastrophic for Turkish long-term rates and the broader economy. As markets recognized the central bank’s subordination to political authority, Turkish lira bond yields soared to over 30%, reflecting expectations of continued high inflation.

Rather than delivering lower borrowing costs, Erdoğan’s interference produced precisely the opposite. Turkey now faces persistent inflation above 40% and long-term rates that make normal economic activity nearly impossible.

Argentina provides another cautionary tale. Decades of central bank subordination to fiscal and political demands have left Argentine long-term interest rates in local currency essentially non-existent—not because they are low, but because markets refuse to lend long-term in pesos at any rate, anticipating continued monetary dysfunction. When long-term peso borrowing does occur, rates reflect triple-digit inflation expectations.

These are extreme cases, but they illustrate a universal principle: politicized monetary policy destroys the credibility necessary for low long-term rates.

The United States would not immediately replicate Turkish or Argentine dysfunction, but movement in that direction would manifest first and most clearly in rising long-term yields as markets price in deteriorating central bank independence.

The Term Premium and Policy Uncertainty

Beyond inflation expectations, long-term rates also incorporate a term premium—additional compensation investors demand for the uncertainty of holding long-duration assets. This term premium reflects multiple sources of risk, but policy uncertainty stands among the most important.

Central bank independence reduces policy uncertainty by creating predictable reaction functions: markets know how the Fed will respond to economic developments because its mandate and institutional culture are clear.

A compromised Fed chair changes this calculus fundamentally. If monetary policy becomes responsive to political demands rather than economic conditions, policy becomes far less predictable.

Will Hassett cut rates because inflation is falling or because Trump wants lower rates before an election? Will he resist cutting despite weak growth because inflation remains elevated, or will political pressure override inflation concerns?

Markets cannot answer these questions with confidence for a chair whose selection was premised on responsiveness to White House preferences.

This uncertainty gets priced into the term premium. Even if markets believe average inflation will remain moderate, the increased variance in possible policy paths requires compensation.

Academic research consistently finds that policy uncertainty raises long-term rates, with effects that can be substantial when independence is seriously questioned.

The Fiscal-Monetary Coordination Problem

The Trump administration’s fiscal trajectory compounds concerns about Fed independence. The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” projects dramatically rising deficits and debt-to-GDP ratios reaching 183-199% by 2054.

Even over the next decade, primary deficits are projected to remain elevated while the debt refinancing needs approach $10 trillion annually.

This fiscal outlook creates pressure for the Fed to keep rates low to reduce debt service costs—a phenomenon economists call “fiscal dominance.”

When government debt is very high, the central bank faces a choice: maintain its inflation-fighting credibility even if that means unsustainable debt dynamics, or accommodate fiscal needs by keeping rates lower than inflation-fighting would require.

A truly independent Fed chair would insist that fiscal sustainability is the government’s responsibility, not the Fed’s, and would set rates according to the inflation mandate regardless of fiscal consequences.

But a chair selected precisely for willingness to coordinate with administration priorities would face intense pressure to consider fiscal factors in rate decisions.

Markets understand this dynamic. The combination of deteriorating fiscal outlooks and a politically-connected Fed chair raises the specter of fiscal dominance—the central bank effectively financing government spending through artificially low rates.

Bond markets price this risk through higher term premiums and inflation expectations, pushing long-term rates up even as the Fed might be cutting short-term rates.

The Short-Term Versus Long-Term Rate Distinction

Understanding why Hassett’s appointment would raise long-term rates while potentially lowering short-term rates requires distinguishing between the two.

The Fed directly controls only very short-term rates—overnight lending rates in the federal funds market. Long-term rates are market-determined, reflecting expectations about future short-term rates, inflation, and various risk premiums over many years.

A dovish Fed chair can certainly push short-term rates lower. Hassett could cut the federal funds rate aggressively, and that rate would indeed fall.

But if markets believe this accommodation will lead to higher inflation in the medium term, they will demand higher yields on long-term bonds to compensate. The result can be lower short-term rates coinciding with higher long-term rates.

This divergence is precisely what occurred in the 1970s and what has characterized emerging markets with compromised central bank independence. Short-term rates might be held artificially low through direct central bank action, but long-term markets price in the consequences of this policy, driving long-term yields up.

For American households and businesses, this is the worst possible outcome. Most consequential borrowing—mortgages, auto loans, corporate bonds, business investment financing—is based on long-term rates, not the federal funds rate.

Even if Hassett succeeded in cutting short-term rates dramatically, rising long-term rates would mean higher, not lower, borrowing costs for the transactions that matter most to economic activity.

The Initial Market Response: A Misread

The initial positive market response to Hassett speculation—falling Treasury yields—likely reflects a misunderstanding of these dynamics. Markets may have focused narrowly on the prospect of near-term rate cuts without fully pricing in the long-term credibility consequences.

Alternatively, the initial response may reflect positioning by traders expecting to sell to less-informed investors later, or simple momentum trading on the headline.

Historical precedent suggests initial positive reactions to central bank subordination typically reverse once the implications become clear.

Turkish markets initially rallied on Erdoğan’s rate-cutting demands before reality set in. Argentine markets have repeatedly responded positively to short-term monetary accommodation before the inflation consequences manifested in higher long-term rates.

More tellingly, Hassett himself seemed to interpret the market response through a simplistic lens: lower yields mean success in delivering cheaper borrowing. But sophisticated fixed-income investors understand the difference between a temporary market reaction and the sustained low long-term rates that require credibility.

Once Hassett begins actual policymaking under Trump’s influence, markets will price in the reality rather than the hopeful speculation.

Conclusion: The Credibility Trap

The Trump administration faces a fundamental contradiction in its approach to Fed leadership. It seeks lower long-term borrowing costs for American households and businesses. But it proposes to achieve this goal by appointing a chair whose primary qualification is loyalty to the president and willingness to subordinate monetary policy to political demands. This strategy will almost certainly backfire.

Low long-term interest rates are not gifts that accommodating central bankers can simply bestow. They are earned through decades of credible commitment to price stability and demonstrated independence from political pressure.

They reflect market confidence that inflation will remain low and that monetary policy will be predictable and rule-based. Appointing Kevin Hassett as Fed chair would undermine precisely these sources of credibility.

The initial market response may prove to be an expensive mistake for those who acted on it. As Hassett’s appointment becomes reality and his policy approach becomes clear, markets will reprice long-term yields to reflect higher inflation expectations, increased policy uncertainty, and concerns about fiscal dominance.

The irony is that the very characteristics that make Hassett attractive to the White House—his closeness to the president and presumed responsiveness to political pressure—are exactly the characteristics that will push long-term rates higher.

Americans seeking lower mortgage rates and cheaper auto loans would be far better served by a Fed chair committed to independence and credibility, even if that means sometimes resisting White House preferences for easier money.

The path to sustainably low long-term rates runs through the boring virtues of central bank independence, not through the false promise of political coordination. Kevin Hassett’s appointment would represent a step away from those virtues—and long-term rates would adjust accordingly.

Brilliant analysis of the independence premium paradox.

Your framing of how markets price central bank credibility really clarifies why short-term accommodation can backfire spectacularly. The core insight here is that long-term rates aren't gifts policymakers bestow, they're market judgments about institutional commitment to price stability. When that commitment appears compromised through political coordination, the term premium expands to reflect both higher inflation variance and policy uncertainty.

What strikes me most is the fiscal dominance angle given current debt trajectories. With refinancing needs approaching $10 trillion annually and debt-to-GDP projections hitting 183-199% by 2054, markets will scrutinize any Fed chair's willingness to prioritize inflation control over debt servicing costs. A chair selected explicitly for White House responsiveness sends exactly the wrong signal at exactly the wrong time.

The historical comparsion to the 1970s Burns era is particularly instructive. We saw the same pattern then: political pressure for accommodation produced not lower borrowing costs but a decade of rising long-term yields as inflation expectations became unanchored. Rebuilding that credibility under Volcker required punishing rates and multiple recessions. Markets remember that lesson even if policymakers sometimes forget it.

Someone should do a dive on the historyof his public views. Presumably his support of One budget Bashing Bill is just standard transfer income to the rich stuff, nothing especially subservinet to Trump in that. But what about tariffs and deportations? That wasn't not standard issue Republican talking points pre Trump. Interestg to know to wht extent he is just sincerely wrong vs displaying sicophancy.