Gambling With the Dollar’s Future

Why American Complacency Could Cost Us Our Greatest Economic Advantage

The United States dollar has reigned supreme as the world’s reserve currency for nearly eight decades, a position that has afforded America what former French Finance Minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing famously termed an “exorbitant privilege.”

This privileged status has allowed the US government to borrow at lower rates than would otherwise be possible, funding everything from wars to social programs with relative ease. However, as Carmen M. Reinhart warns, a dangerous complacency has settled over American policymakers regarding this advantageous position.

With ballooning deficits, inflation risks, and the fragmentation of global trade, the United States may be gambling with its monetary future in ways that could prove disastrous.

The Foundation of Dollar Dominance

Since emerging from World War II as the world’s preeminent economic and military power, the United States has enjoyed the unique position of having its currency serve as the primary medium for international trade and the preferred reserve asset for central banks worldwide.

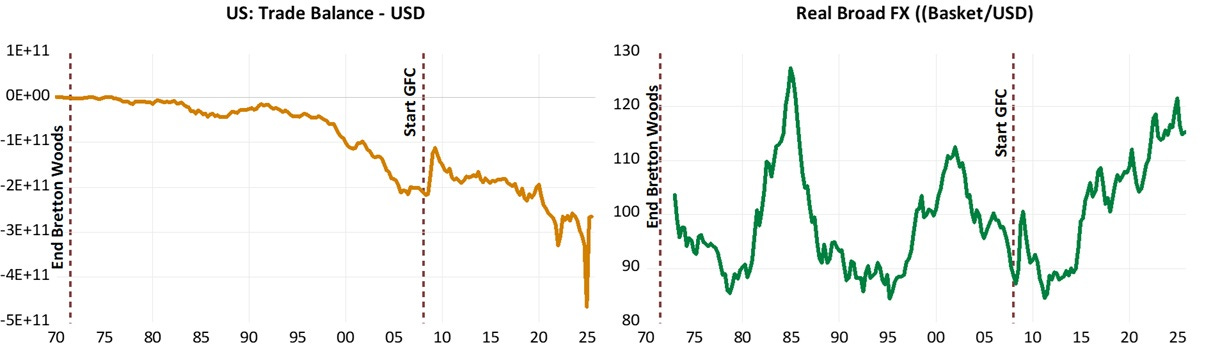

This status was formalized through the Bretton Woods system and, even after that system’s collapse in 1971, the dollar maintained its dominance through sheer economic momentum, deep and liquid financial markets, and the absence of viable alternatives.

The benefits of this arrangement are substantial and multifaceted. When foreign central banks and private investors view US Treasury securities as the safest asset available, they create persistent demand for dollar-denominated debt. This demand allows the US government to finance its operations at interest rates lower than fundamentals might otherwise suggest.

In practical terms, this means American taxpayers pay less to service the national debt, and the government enjoys greater fiscal flexibility than other nations of comparable or even superior fiscal health.

Beyond lower borrowing costs, dollar dominance facilitates American consumption beyond what the nation produces. The United States has run persistent current account deficits for decades, importing more than it exports, yet this imbalance has been sustainable precisely because other nations are willing to accumulate dollar assets.

American consumers and businesses benefit from this arrangement through access to cheaper goods and services, while American financial institutions profit from their central role in global financial intermediation.

The Growing Threats

However, multiple emerging threats now challenge the sustainability of this arrangement, and policymakers’ apparent indifference to these dangers constitutes a form of high-stakes gambling with the nation’s economic future.

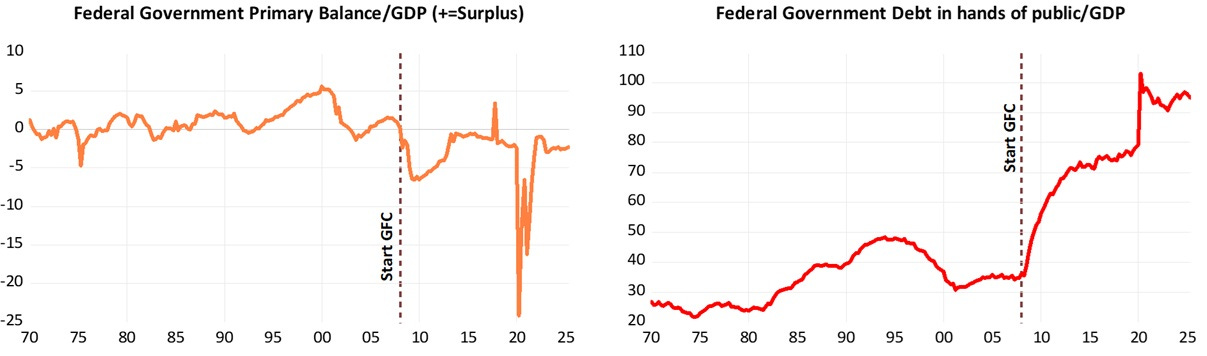

First and foremost among these threats is the trajectory of US fiscal policy. The national debt has grown substantially as a percentage of GDP, driven by recurring deficits that show no signs of abating.

While politicians from both parties pay lip service to fiscal responsibility, actual policy choices tell a different story. Tax cuts are politically popular, entitlement programs are politically untouchable, and defense spending enjoys bipartisan support. The result is a structural deficit that persists regardless of which party controls the government.

Under normal circumstances, such fiscal profligacy would trigger market discipline. Investors would demand higher interest rates to compensate for increased risk, forcing governments to either curtail spending or raise taxes.

But the dollar’s reserve status has thus far insulated the United States from such discipline, creating a moral hazard that encourages further fiscal irresponsibility.

Policymakers have learned they can run large fiscal deficits without immediate consequences, but this lesson may prove disastrously incomplete if the dollar’s privileged status erodes.

The second major threat comes from inflation risk. While inflation has moderated from its post-pandemic peaks, the underlying factors that drove prices higher remain relevant concerns.

Supply chain disruptions impacting a broad swath of relative prices and expansive monetary policy combined to produce the highest inflation rates in four decades. Although central banks have responded adequately, the inflation genie may not be fully back in the bottle.

Should inflation prove more persistent or recurring than currently anticipated, the real value of dollar-denominated assets would erode, making them less attractive to foreign holders. Central banks that hold substantial dollar reserves would see the purchasing power of those reserves diminish, potentially prompting a gradual shift toward alternative assets.

The third threat stems from the ongoing fragmentation of global trade. The post-Cold War consensus around free trade and economic integration has fractured. The United States itself has moved toward greater protectionism, imposing tariffs and restricting trade with geopolitical rivals.

Meanwhile, China has worked to internationalize its currency and establish alternative payment systems that bypass dollar-based infrastructure. Regional trade blocs are forming that may eventually develop their own preferred currencies for intra-regional transactions.

While none of these developments immediately threatens dollar dominance, they collectively chip away at the network effects that have sustained it.

The Complacency Problem

What makes the current situation particularly concerning is not merely the existence of these threats, but the apparent complacency with which American policymakers regard them. There seems to be an implicit assumption that the dollar’s dominance is permanent, an immutable feature of the global economic landscape rather than a contingent arrangement dependent on continued confidence and prudent policy.

This complacency manifests in several ways. Fiscal policy proceeds as if unlimited borrowing at low rates will always be available. Political leaders speak of the national debt as an abstract concern for future generations rather than a present danger.

There is little serious discussion of how specific policy choices might affect international confidence in dollar assets. The implicit assumption seems to be that America’s “exorbitant privilege” is simply the natural order of things.

History suggests otherwise. Reserve currency status is not permanent. The British pound sterling once held the position the dollar now occupies, yet Britain’s fiscal problems and relative economic decline eventually cost it that status.

While no immediate candidate exists to supplant the dollar—the euro suffers from structural problems within the eurozone, the yuan lacks the necessary financial infrastructure and openness, and other currencies are simply too small—the absence of an obvious alternative does not guarantee the dollar’s continued dominance.

Reserve currency transitions can happen gradually, with the incumbent currency losing ground to a basket of alternatives rather than a single successor.

The Stakes

The potential consequences of losing reserve currency status would be profound. Most immediately, the US government would face higher borrowing costs, requiring either spending cuts, tax increases, or both—painful adjustments that would affect every aspect of American life.

The ability to run persistent current account deficits would be constrained, requiring Americans to consume less relative to what they produce. Financial institutions would lose some of their central role in global finance, affecting employment and profitability in an important economic sector.

More broadly, diminished reserve currency status would reduce American geopolitical influence. The ability to impose financial sanctions derives largely from the dollar’s central role in global finance. If transactions can easily bypass dollar-denominated systems, this tool of statecraft loses much of its effectiveness.

The soft power that comes from running the global financial system would similarly erode.

The Path Forward

Addressing these challenges requires abandoning complacency in favor of deliberate policy choices aimed at preserving confidence in dollar assets. This means, first and foremost, developing a credible path toward fiscal sustainability. While the appropriate pace of deficit reduction is debatable—too rapid consolidation could harm economic growth—the trajectory of current policy is clearly unsustainable and risks eventually triggering a crisis of confidence.

It also requires monetary policy that maintains price stability over the long term, even when short-term political pressures push toward easier policy. The Federal Reserve’s independence must be jealously guarded, as any politicization of monetary policy would undermine confidence in the dollar’s value.

Finally, the United States should recognize that its economic privileges are not entitlements but rather outcomes that depend on continued confidence and sound policy. The dollar’s reserve status is an asset to be carefully maintained, not a permanent feature to be taken for granted. Gambling with the dollar’s future through complacent policymaking is a risk the nation can ill afford to take.

The stakes are simply too high, and the warning signs too clear, for policymakers to continue assuming that America’s “exorbitant privilege” will endure regardless of the choices they make today. The time for complacency has passed; the time for deliberate, thoughtful policy aimed at preserving the dollar’s status is now.

Unfortunately, Trump´s policies makes this highly unlikely to achieve!

All of this s true and worth saying, but the policies that would lead to the loss of dollar dominance are themseves much worse than the loss.

"Don't drive like a maniac and total your car, it will _ruin_ the paint job!"

And BTW, the actual benefit to the US from "dollar dominance" is the dminace of US firms in managing the world's interntional transactions and investments, not the discount at whihc the USG can borrow.

https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/the-dollar-privilege-or-burden

For Dollar to be replaced, wouldn't the vast stock of dollar denominated debt worldwide first need to be repaid?

Which for now is only growing