(Note: This post was written 7 years ago. I repost it here because I believe it´s the “final irony” surrounding Ben)

To my mind, Bernanke is the living embodiment of irony. Irony has followed him closely through the last few decades. Below a small but diverse sample.

What Happens when Greenspan is gone? (Jan 2000):

U .S. monetary policy has been remarkably successful during Alan Greenspan’s 121/2 years as Federal Reserve chairman. But although President Clinton yesterday reappointed the 73-year-old Mr. Greenspan to a new term ending in 2004, the chairman will not be around forever. To ensure that monetary policy stays on track after Mr. Greenspan, the Fed should be thinking through its approach to monetary policy now. The Fed needs an approach that consolidates the gains of the Greenspan years and ensures that those successful policies will continue; even if future Fed chairmen are less skillful or less committed to price stability than Mr. Greenspan has been.

We think the best bet lies in a framework known as inflation targeting, which has been employed with great success in recent years by most of the world’s biggest economies, except for Japan. Inflation targeting is a monetary-policy framework that commits the central bank to a forward-looking pursuit of low inflation; the source of the Fed’s current great performance; but also promotes a more open and accountable policy-making process. More transparency and accountability would help keep the Fed on track, and a more open Fed would be good for financial markets and more consistent with our democratic political system.

He was what happened, and he did exactly what he said should be done. Was it a success? To be kind, not so much.

Systematic MP and the effects of oil price shocks (June/1997):

Substantively, our results support that an important part of the effect of oil price shocks on the economy results not from the change in oil price per se, but from the resulting tightening of monetary policy.

This finding may help explain the apparently large effects of oil price changes found by Hamilton (1983) and many others.

Soon after becoming Chairman of the BoG an oil shock materialized. What did Bernanke do? He forgot about his “findings” and tightened monetary policy (constraining NGDP growth (see below)).

On Milton Friedman´s 90th Birthday (Nov 2002):

Once Roosevelt was sworn in, his declaration of a national bank holiday and, subsequently, his cutting the link between the dollar and gold initiated the expansion of money, prices, and output.

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.

He did it, albeit at a much smaller scale. Why? Because he acted on his “knowledge” of the “credit channel”. From his 1983 article Non-Monetary Factors of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression:

A second possibility is that banking panics contributed to the collapse of output and prices through nonmonetary mechanisms. My own early work (Bernanke, 1983) argued that the effective closing down of the banking system might have had an adverse impact by creating impediments to the normal intermediation of credit, as well as by reducing the quantity of transactions media.

That was what propagated the depression. By “saving” the banks, Bernanke´s Fed “cut-off the propagation mechanism”, leaving only the deleterious effects of the monetary policy mistakes.

What were those mistakes? An idea comes from On the legacy of Milton and Rose Friedman´s Free to Choose (2003):

As emphasized by Friedman (in his eleventh proposition) and by Allan Meltzer, nominal interest rates are not good indicators of the stance of policy, as a high nominal interest rate can indicate either monetary tightness or ease, depending on the state of inflation expectations. Indeed, confusing low nominal interest rates with monetary ease was the source of major problems in the 1930s, and it has perhaps been a problem in Japan in recent years as well. The real short-term interest rate, another candidate measure of policy stance, is also imperfect, because it mixes monetary and real influences, such as the rate of productivity growth…

The absence of a clear and straightforward measure of monetary ease or tightness is a major problem in practice. How can we know, for example, whether policy is “neutral” or excessively “activist”?

Ultimately, it appears, one can check to see if an economy has a stable monetary background only by looking at macroeconomic indicators such as nominal GDP growth and inflation…

Unfortunately, he preferred to concentrate on inflation, and worse, the headline variety, which was being buffeted by the oil and commodity price shocks! Apparently, inflation is not always a good indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

Japanese Monetary Policy: A case of self-induced paralysis (Dec 1999):

Before discussing ways in which Japanese monetary policy could become more expansionary, I will briefly discuss the evidence for the view that a more expansionary monetary policy is needed. As already suggested, I do not deny that important structural problems, in the financial system and elsewhere, are helping to constrain Japanese growth. But I also believe that there is compelling evidence that the Japanese economy is also suffering today from an aggregate demand deficiency. If monetary policy could deliver increased nominal spending, some of the difficult structural problems that Japan faces would no longer seem so difficult.

It is true that current monetary conditions in Japan limit the effectiveness of standard open-market operations. However, as I will argue in the remainder of the paper, liquidity trap or no, monetary policy retains considerable power to expand nominal aggregate demand. Our diagnosis of what ails the Japanese economy implies that these actions could do a great deal to end the ten-year slump.

Japan is not in a Great Depression by any means, but its economy has operated below potential for nearly a decade. Nor is it by any means clear that recovery is imminent. Policy options exist that could greatly reduce these losses. Why isn’t more happening? To this outsider, at least, Japanese monetary policy seems paralyzed, with a paralysis that is largely self-induced. Most striking is the apparent unwillingness of the monetary authorities to experiment, to try anything that isn’t absolutely guaranteed to work. Perhaps it’s time for some Rooseveltian resolve in Japan.

Twelve years later, “Rooseveltian Resolve” was asked of him by Christina Romer in

Dear Ben: It’s Time for Your Volcker Moment (2011):

For evidence that adopting the new target could help fix the economy, look at the 1930s. Though President Franklin D. Roosevelt didn’t talk in terms of targeting nominal G.D.P., he spoke of getting prices and incomes back to their pre-Depression levels. Academic studies suggest that this commitment played an important role in bringing about recovery.

President Roosevelt backed up his statements. He suspended the gold standard and let the dollar depreciate. He got Congress to pass New Deal spending legislation and had the Treasury monetize a large gold inflow. The result was an end to deflationary expectations , leading to the most impressive swing the country has ever seen from horrible contraction to rapid growth.

Would nominal G.D.P. targeting work as well today? There would likely be unexpected developments, just as there were in the Volcker period. But the new target would have a better chance of meaningfully reducing unemployment than any other monetary policy under discussion.

Because it directly reflects the Fed’s two central concerns — price stability and real economic performance — nominal G.D.P. is a simple and sensible target for long after the economy recovers. This is very different from Mr. Volcker’s money target, which was abandoned after only a few years because of instability in the relationship between money growth and the Fed’s ultimate objectives.

Desperate times call for bold measures. Paul Volcker understood this in 1979. Franklin D. Roosevelt understood it in 1933. This is Ben Bernanke’s moment. He needs to seize it.

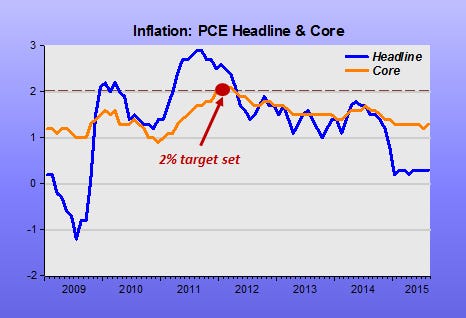

Romer´s article was published Oct 29/11. Just 3 days later, the FOMC met. They discussed NGDPT, but rejected it and 2 months later Bernanke realized his longtime dream: IT became official @2%!

Again he forgot. This time his advice to Japanese monetary authorities. Final irony: when was inflation last at 2%? On the month (Jan/12) 2% became the target!

Thanks for saying it. As subtlety is not a gift to have ever been bestowed upon me, I was focused on ignoring the latest "irony". Congratulations to Bernanke, anyway. Perhaps he can use the latest prestige to do great good in the world.

And Bernanke contends: “a flawed and over-simplified monetarist doctrine that posits a direct relationship between the money supply and prices" (in his book "21st Century Monetary Policy").