To many, inflation is the virulent cancer spreading out very quickly over the economic fabric. In fact, even to those that do not mention money in there analysis, the world is fast going downhill. Two recent examples can be found by reading Roubini (The Gathering Stagflationary Storm) and Rogoff (The Growing Threat of Global Recession).

I´m among those who firmly believe that inflation is a monetary (policy) phenomenon, not due to structural changes or even (usually) to fiscal policy.

Nevertheless, even to those who believe inflation has monetary origins, things are not so straightforward. Certainly no one doubts Milton Friedman´s beliefs in the monetary origins of inflation. However, in 1983, and that´s just after we left behind the era of the Great Inflation, this was Friedman´s perspective.

Milton Friedman in 1983:

It seemed to us that “this monetary explosion assures vigorous economic growth in the coming months”—but also that “unfortunately, if it continues much longer, it will also produce a renewed acceleration of inflation and a sharp rise in interest rates.”

The monetary explosion did produce vigorous growth. Unfortunately, it also did continue… Interest rates have already risen sharply. Inflation has not yet accelerated. That will come next year, since it generally takes about two years for monetary acceleration to work its way through to inflation.

…The monetary explosion from July 1982 to July 1983 leaves no satisfactory way out of our present situation. The Fed’s stepping on the brakes will appear to have no immediate effect. Rapid recovery will continue under the impetus of earlier monetary growth.

With its historical shortsightedness, the Fed will be tempted to step still harder on the brake—just as the failure of rapid monetary growth in late 1982 to generate immediate recovery led it to keep its collective foot on the accelerator much too long. The result is bound to be renewed stagflation—recession accompanied by rising inflation and high interest rates.

Coincidentally, on the very same day that Friedman´s Newsweek column was published, William Barnett, the person behind the development of Divisia Monetary Indices gave an interview to Forbes “What Explosion?”:

…The other conclusion is that people have been panicking unnecessarily about money supply growth this year. The new bank money funds and the super NOW accounts have been sucking money that was formerly held in other forms…But Divisia aggregates are rising not much different from last year. Thus, the apparent “explosion” can be viewed as a statistical blip.

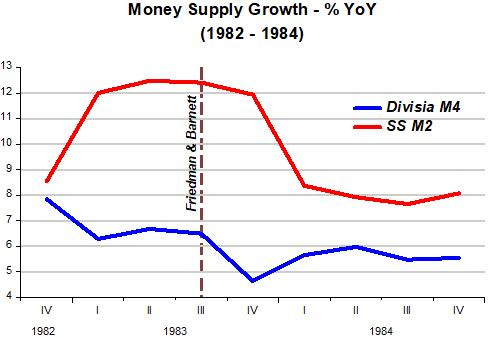

The chart below clearly shows that they were talking about very different “beasts”!

And inflation continued to drop and growth remained robust into 1985 and 1986! So Friedman´s view that “The result is bound to be renewed stagflation” never materialized.

Jumping to the present, Peter Ireland has just channeled Friedman in “The Recent Surge in Money Growth: What would Milton Friedman Say?”:

Nevertheless, Friedman surely would be alarmed by the recent surge in M2 growth. One can, in fact, use insights gleaned from Friedman’s research to see that although the statistical relationships between money growth, real GDP growth, and inflation may have weakened somewhat in recent decades, they have in no way disappeared. Thus, rapid M2 growth serves as a warning sign. Unless the Federal Reserve acts soon and decisively to recalibrate its monetary policy strategy, higher inflation will quite likely persist.

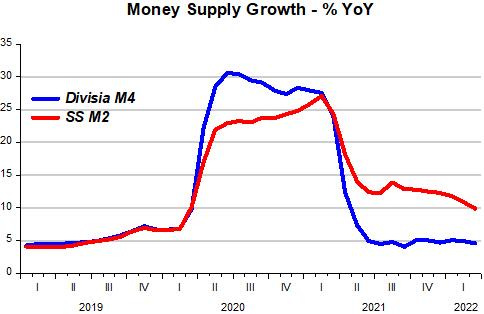

The corresponding chart shows that for almost a year now, Simple Sum M2 has grown at more than double the rate of growth of Divisia M4 (which has remained very close to 5% YoY).

It should be noted that Friedman´s “it generally takes about two years for monetary acceleration to work its way through to inflation” still remains “popular”. In Spring 2020, just as money growth surged (with Divisia M4 growth peaking at 30% in June 20), Tim Congdon, a well known British monetarist, asked: “Will the current money growth acceleration increase inflation?” My retort was “Will the current money growth acceleration help avoid a second Great Depression?”.

I believe I asked the better question because, in fact, given the mammoth drop in velocity, that surge in money growth was exactly what was required, being the reason the recession, although deep, was the shortest recorded and the recovery a very fast one!

During the Great Inflation, Divisia M4 growth peaked at 10% while Core PCE inflation also peaked at 10%. Given the 2 year rule of thumb, core PCE inflation should be climbing above 20% a year by now! It certainly hasn´t. In February it reached 5.3% YoY while in March it ticked down to 5.2%!

It appears the Fed has learned a bit more about “navigating in the face of complex shocks”. And the pandemic was a complex shock with both supply and demand “crosswinds”, that still persist (and may get stronger going forward with the introduction of an additional “crosswind” emanating from the “Russian War”).

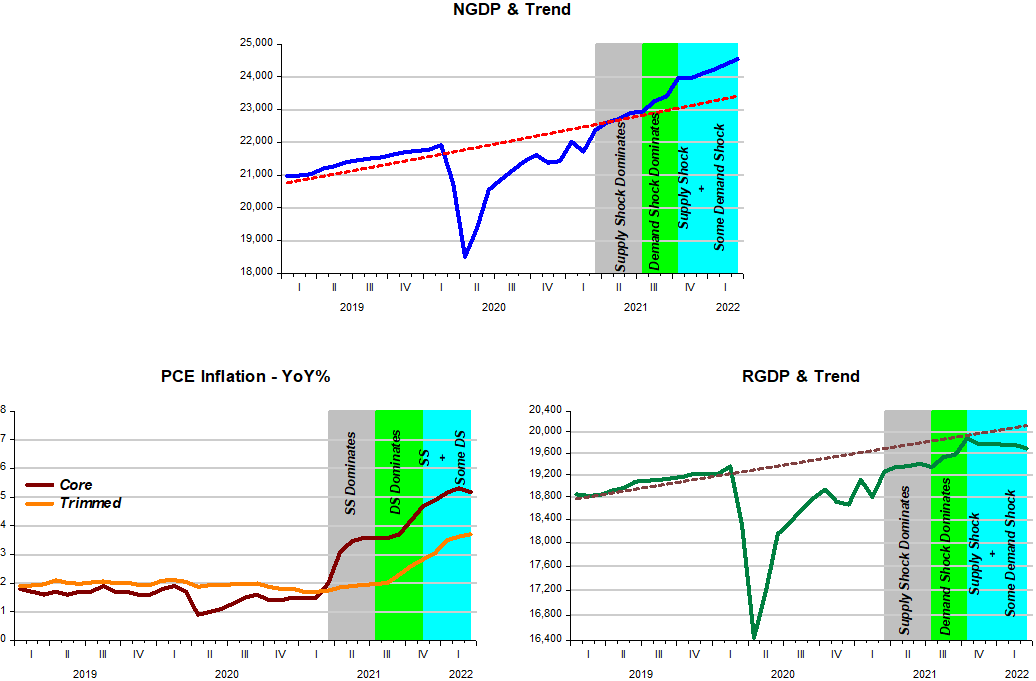

The chart below shows how the Fed has behaved (and is behaving), and the implications for inflation (interpret the trimmed mean PCE as a “supercore” index).

The “driving force” is monetary policy, as reflected in the behavior of aggregate nominal spending (NGDP). If NGDP is falling, monetary policy is tightening. If it is rising, monetary policy is expansionary. The “trick” is for the Fed to conduct monetary policy so as to obtain Nominal Stability, by which I mean “keeping NGDP evolving close to the stable trend path”.

The colored bars make reading and interpreting the charts easier. Note that by March 2021, NGDP reached the trend path (that begins right after the end of the Great Recession). It stays on the path until July 21. During those months, RGDP stays flat, while some measures of inflation begin to rise, indicating that when NGDP reached trend, the supply constraints became binding.

That´s the “classic” outcome from a supply shock: Inflation increases and real output drops (in this case does not rise to trend due to supply constraints). That first round of inflation was the inevitable consequence of the supply shock. Nominal stability required that NGDP remain on the trend path).

After July 21, NGDP rises above trend (green bar), monetary policy becomes expansionary so demand shocks predominate. The “classic” outcome from a demand shock is what´s observed: an increase in the rate of inflation and an increase in real output (that climbs toward trend).

By October 21, the Fed appears to have recognized that it “overplayed” its hand, so NGDP “calms down”, leading inflation to also “taper off” somewhat. Real output drops because of renewed prevalence of supply constraints.

From the NGDP perspective above, how the Fed acts going forward is what will define growth and inflation. Some have more reasonable views. This from a tweet by Tim Duy:

Forgotten in the near term hawkishness is that we likely passed peak inflation and the issue is whether we end the year closer to 4% or 2%.

Many think the Fed should quickly increase interest rates, while others believe the Fed should “immediately” correct its previous mistake and bring NGDP back to trend.

These “solutions” would likely do more harm than good. My preferred alternative is for the Fed to keep NGDP as close as possible to the 24 trillion dollars level it clocks at the moment until it “meets” the trend path down the road. In the process, NGDP growth will be falling, curtailing the part of inflation due to demand and minimizing the adverse effects of supply shocks.

Your advice to the Fed? Talk tough, act soft? Or is talking also acting?