"A tale of two moments"

In the first the Fed got it right. It didn´t manage to do an encore a few years later

While preparing for something else, I was reminded of the success of the Fed´s Forward Guidance introduced in mid-2003.

Going into that moment, the “fear” was of deflation:

In 2002 things came to a head. Greenspan made the first move in a speech on November 13:

There is an implication that the notion (of fighting deflation risks) that we are restricted solely to overnight funds. But our history as an institution indicates that there have been innumerable occasions when we have moved out from short-term assets and invested in long term Treasuries. We do have the capability, if required to do so, to go well beyond activities related to short-term rates.

This was followed by Bernanke´s famous “Deflation: making sure “it” doesn´t happen here” speech one week later. He asks:

So what then might the Fed do if its target interest rate, the federal funds rate, fell to zero”? One answer: One approach, similar to an action taken in the past couple of years by the Bank of Japan, would be for the Fed to commit to holding the overnight rate at zero for some specified period…” Another: “A more direct method, which I personally prefer, would be for the Fed to begin announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer maturity Treasury debt…

When the time came to act, in August 2003, however, the Fed did not mention interest rate (short or long rates), using the more generic “policy accomodation”. From what transpired a few years later, if they had they might have not succeeded!

The Committee perceives that the upside and downside risks to the attainment of sustainable growth for the next few quarters are roughly equal. In contrast, the probability, though minor, of an unwelcome fall in inflation exceeds that of a rise in inflation from its already low level. The Committee judges that, on balance, the risk of inflation becoming undesirably low is likely to be the predominant concern for the foreseeable future. In these circumstances, the Committee believes that policy accommodation can be maintained for a considerable period.

The “for a considerable period” language remained a feature of the statements following the next FOMC meetings in September, October and December 2003.

After the January 2004 meeting a new signal was provided in the statement:

The Committee perceives that the upside and downside risks to the attainment of sustainable growth for the next few quarters are roughly equal. The probability of an unwelcome fall in inflation has diminished in recent months and now appears almost equal to that of a rise in inflation. With inflation quite low and resource use slack, the Committee believes that it can be patient in removing its policy accommodation.

Indicating that the moment that rates would start rising had been brought forward.

The language remained the same in the March 2004 FOMC meeting. But after the May 2004 meeting another signal was given:

The Committee perceives the upside and downside risks to the attainment of sustainable growth for the next few quarters are roughly equal. Similarly, the risks to the goal of price stability have moved into balance. At this juncture, with inflation low and resource use slack, the Committee believes that policy accommodation can be removed at a pace that is likely to be measured.

The FOMC in effect was saying: Time´s up, but stay calm because the FF rate is not going to jump up!

On cue, the rate was raised by 25 basis points (0.25 percentage points) in the June 2004 meeting and the words at a pace that is likely to be measured remained. And it was so all the way to Greenspan´s farewell FOMC meeting on January 31, 2006, when the FF rate was raised another 25 basis points to 4.5%.

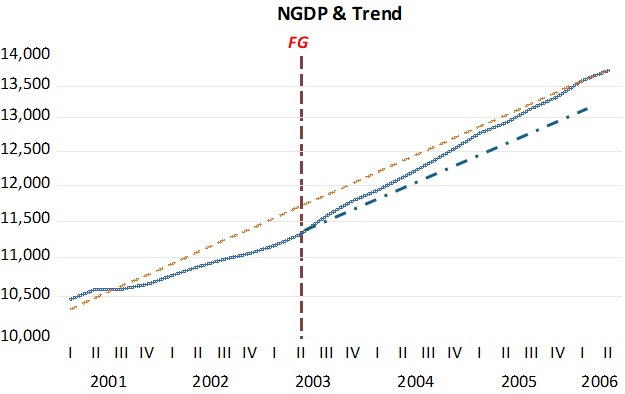

All this “guidance” was very successful, as the charts below indicate.

The first chart shows that NGDP, which had fallen significantly below the Great Moderation trend level path since the 2001 recession, picked up (immediately, no lags).

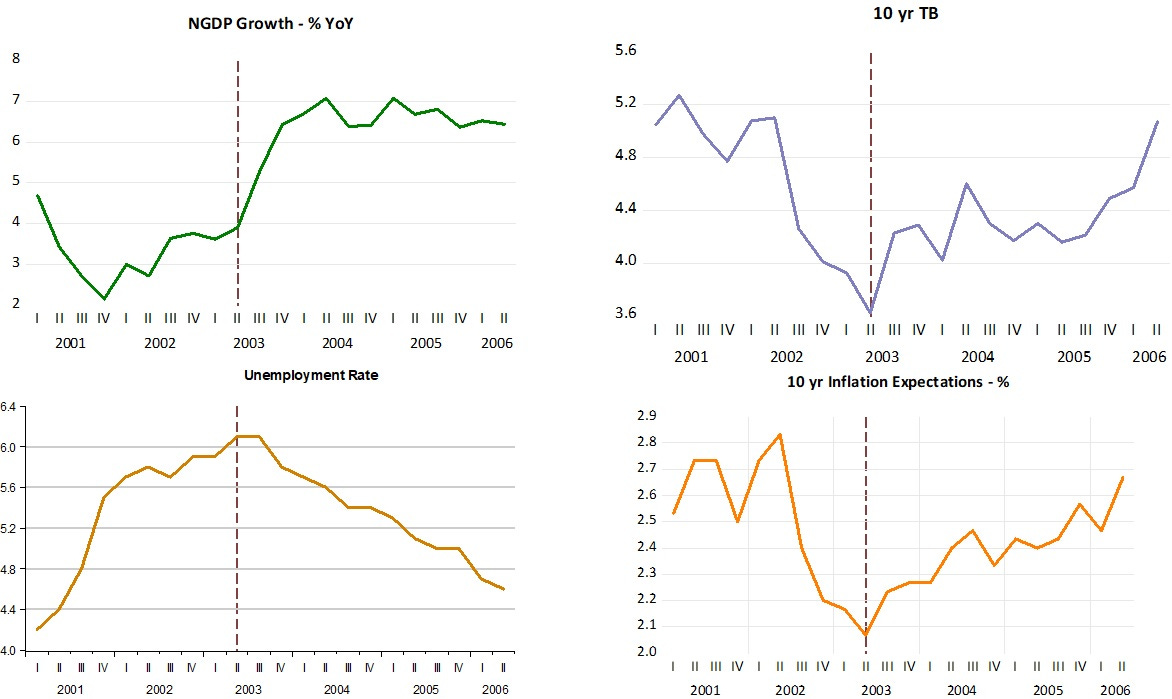

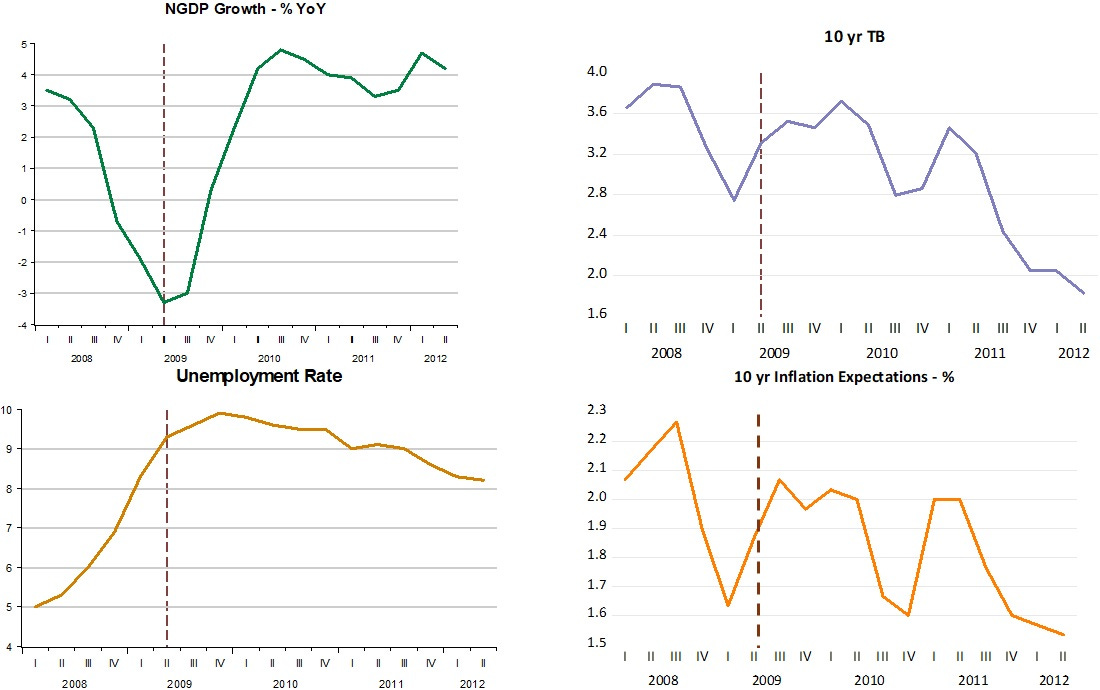

The panel below shows what happened to a set of “worrying” variables.

NGDP grew robustely, the only way to bring the level of spending back to the trend path. Unemployment fell (real growth rose), long rates increased (not fall), evidence that, contrary to Fed thinking (note Greenspan and Bernanke above), interest rates do not define the stance of monetary policy. The fear of deflation disappeared, with inflation expectations going up (as desired).

“Policy accomodation” was successful. At the end of this period, Bernanke took over the helm of the Fed. It didn´t take long for Bernanke´s “inflation fetish”, in this case emanating from oil price shocks, to assert itself, with dire consequences.

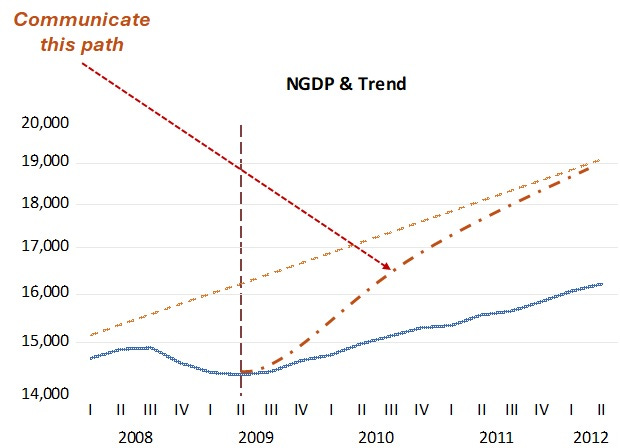

The first chart shows that the level of Aggregate Nominal Spending (NGDP) tanked and the FEd Funds rate was at the ZLB. Rmemember that in 2002 Bernanke asked:

So what then might the Fed do if its target interest rate, the federal funds rate, fell to zero? And answered:

…A more direct method, which I personally prefer, would be for the Fed to begin announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer maturity Treasury debt…

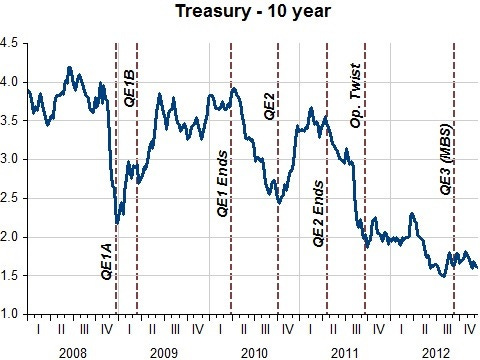

And through Quantitative Easing (QE) he tried hard, with zero success. The second chart below shows clearly that as the QE programs were introduced, long rates rose, falling when the program was discontinued!

The result was that NGDP remained at a depressed level!

The other variables of interest indicate, contrary to what happened after the 2003 Forward Guidance, that there was no recovery, with the economy remaining depressed!

NGDP growth picked up, but at a rate far below that needed to take NGDP back to the previous trend path, just managing to keep NGDP at a lower level path and growing at a reduced rate.

Unemployment remaind high (real growth low), long rates fell (a sign of little enthusiasm with the economy) and inflation expectations dropped.

Surprisingly, at the time, for many Bernanke was hailed as “The Savior”, having managed to avoid a second Great Depression! The fact was he didn´t understand Monetary Policy, always thinking it was associated with interest rates.

N-gDp is a subset of money flows, M*Vt, in American Yale Professor Irving Fisher's truistic "equation of exchange" (total physical transactions, T, that finance both goods and services).

N-gDp is determined by the volume of goods & services coming on the market relative to the actual, transactions, flow of money. Thus M*Vt serves as a “guidepost” for N-gDp trajectories.

The rate-of-change in M*Vt didn't bottom until Nov. 2002. The stock market bottomed during the same time frame. I.e., N-gDp didn't bottom until Greenspan eased monetary policy.

The rate-of-change in M*Vt didn't bottom until March 2009. That's also when the stock market bottomed.

So, it is obvious that these Chairman ignored the course of N-gDp.

re: "Interest rates do not define the stance of monetary policy"

Exactly, Greenspan never tightened, and Bernanke never eased. Every interest rate move was "behind the inflationary curve". Monetarism involved controlling total legal reserves and reserve ratios.

But as Dr. Richard G. Anderson, the world's leading authority on bank reserves said in 2006 "There is general agreement that, for almost all banks throughout the world, statutory reserve requirements are not binding." They weren't binding on the expansion of credit and new money, but they definitely were on the downside. Bankrupt u Bernanke caused the GFC all by himself. Bernanke drained legal reserves until he created a recession.

The fallout was so bad that the commercial banking system experienced the first contraction of credit since the GD. It was so because the welfare of the DFIs is dependent upon the welfare of the NBFIs. The remuneration of interbank demand deposits decimated the NBFIs as the payment of interest was at a level that exceeded short-term interest rates which was explicitly illegal per the FSRRA of 2006. That is, we had a severe "credit crunch" or a destruction in the velocity of circulation, the curtailment in the activation of savings.

Apparently, Bernanke was scared of the explosion in excess reserves he created:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EXCRESNS

Bernanke still has no idea that he "did it again".