The “inflation debate” is no longer between “team temporary & team persistent” as it was in mid-21, but between “team supply & team demand” forces.

I highlight three takes. The first is the most “hysterical”, written by John Cochrane and entitled “The end of an economic illusion”. To Cochrane,

Inflation’s return marks a tipping point. Demand has hit the brick wall of supply. Our economies are now producing all that they can. Moreover, this inflation is clearly rooted in excessively expansive fiscal policies. While supply shocks can raise the price of one thing relative to others, they do not raise all prices and wages together.

And he writes on “secular stagnation”, excessive regulation and climate change.

Jason Furman is much more “composed”, writing “This inflation is demand driven and persistent”:

Commentators have generally offered two arguments about advanced economies’ performance since COVID-19 struck, only one of which can be true.

The first is that the economic rebound has been surprisingly rapid, outpacing what forecasters expected and setting this recovery apart from the aftermath of previous recessions.

The second argument is that inflation has reached its recent heights because of unexpected supply-side developments, including supply-chain issues like semiconductor shortages, an unexpectedly persistent shift from services to goods consumption, a lag in people’s return to the workforce, and the persistence of the virus.

The first argument is more likely to be true than the second. Strong real (inflation-adjusted) GDP growth suggests that economic activity has not been significantly hampered by supply issues, and that the recent inflation is mostly driven by demand. Moreover, there is reason to expect demand to remain very strong, which means that inflation will persist.

In a tweet he summarizes the argument thus:

It is common when talking about GDP to talk about how rapid growth has been: Faster than the past, faster in US than in other countries, faster than forecasters expected, just plain fast.

But this is in serious tension with the supply-side arguments people make on inflation.

The third piece is a technical one from the New York Fed Liberty Street Economics; “Inflation Persistence: How Much Is There and Where Is It Coming From?” In concluding, they argue:

The ups and downs of inflation were transitory, sector-specific until early 2021, but sometime in the fall of 2021, that changed -- and trend inflation rate rose. Sector-specific playing a smaller role.

The model I find most useful when it comes to analyze growth and inflation is the dynamic aggregate demand aggregate supply model. According to the model, in the case of a supply shock output and inflation will move in opposite directions, while in the case of a demand shock, both output and inflation will move in the same direction.

The model also tells us that, in the case of a supply shock, the Fed (monetary policy) should not react to the resulting increase in inflation, but strive to keep aggregate nominal spending (NGDP) growth stable. Otherwise, it would cause unwanted instability.

The Covid-19 shock was both a demand and supply shock. Initially, the demand shock - a sudden & deep drop in velocity - predominated, so that both real output and inflation fell. The Fed was quick to react to the resulting drop in aggregate nominal spending. With that, both NGDP and RGDP began to travel back to their trend level path.

That´s the reason Furman says: “the economic rebound has been surprisingly rapid, outpacing what forecasters expected and setting this recovery apart from the aftermath of previous recessions.”

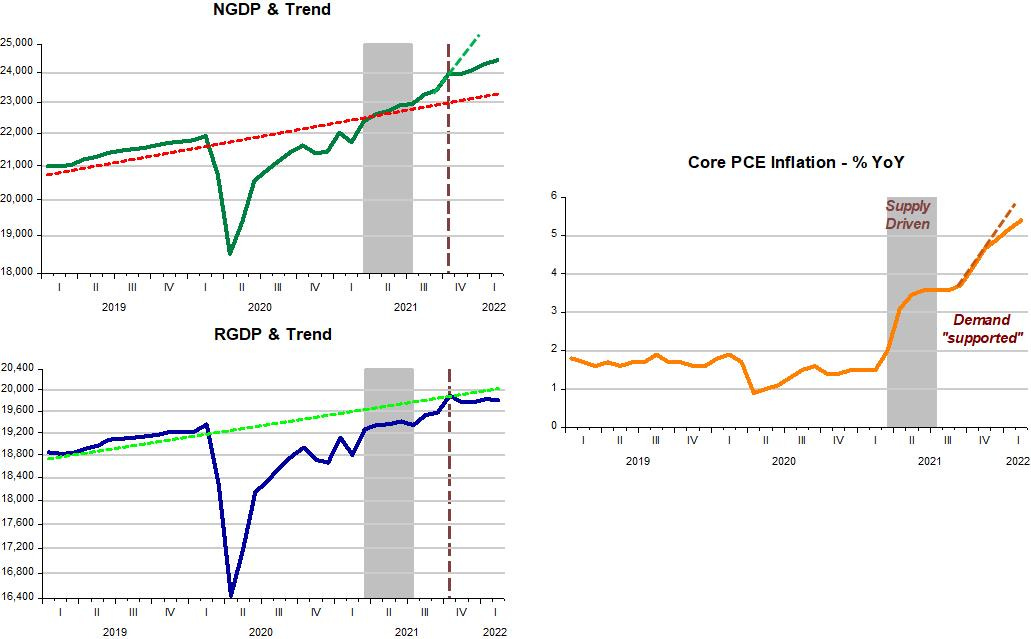

The set of charts below illustrate. They perfectly reflect the model´s predictions, permitting a “precise” breakdown of the inflation being experienced.

Initially, Covid-19 was predominantly a demand shock. The drop in NGDP was both abrupt and deep, bringing both RGDP and inflation down.

The quick reaction by the Fed, increasing the money supply to offset the fall in velocity, acted to quickly reverse the fall in NGDP, thus also promoting a quick recovery of RGDP.

Note that while NGDP goes back to the previous trend, RGDP remains below the trend, capped, as it were, by the supply constraints that at that point became binding.

At this point (March 21), there was only the supply shock from Covid-19 “outstanding”. The inflation that appeared at that point was all due to the Covid-19 generated supply constraints.

In July 21, monetary policy became expansionary, raising NGDP above trend. Note that both RGDP and inflation rise. That´s indicative of a demand shock. After October 21, the rise in NGDP “relents” (see the kink in the NGDP line). RGDP drops below trend and inflation “decelerates”.

From the charts, we can infer that if NGDP had remained on trend after mid-21, inflation would have remained higher until the supply constraints wore off. By increasing NGDP, the Fed “added” a demand shock to the prevailing supply constraints, introducing, as predicted by the Dynamic AS/AD model, some instability.

Regarding the three pieces linked at the beginning, Cochrane´s is wrong when he says “this inflation is clearly rooted in excessively expansive fiscal policies”. I just showed that it is due to monetary policy being excessively expansionary.

Jason Furman´s take that the rapid growth experienced following the Covid-19 shock “is in serious tension with the supply-side arguments people make on inflation”, is not true. The supply-side argument is a fact. What we got, after the recovery was complete (NGDP on trend), given the supply constraints present, was an excessively expansionary monetary policy.

Liberty Street Economics, using more technical tools, reaches essentially the same conclusion as I do: “The ups and downs of inflation were transitory, sector-specific until early 2021, but sometime in the fall of 2021, that changed -- and trend inflation rate rose. Sector-specific playing a smaller role.”

As pointed out in the NGDP chart above, it was in the fall (July) that monetary policy became expansionary and trend inflation rate rose.

In my view, given the uncertainties present, especially the possibility of additional supply constraints from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and renewed Covid-19 related lockdowns in China, for example, the Fed should not completely undo its earlier mistake and “force” NGDP back to the trend path.

We observe in the charts that by simply “stopping” the rising trend in NGDP (the vertical line in October 21), inflation loses “momentum”. If the Fed, going forward, manages to keep NGDP on a “flat line” (close to 24 trillion) until NGDP reaches the rising trend path further down the road, the demand “support” to inflation will keep being reduced while we wait for the waning of existing and any additional supply constraints. As indicated by Liberty Street Economics, what we want is for the Fed to “neutralize” the “trend inflation”.

As I concluded in my previous post: Is that possible? Yes. Will the Fed manage the “trick”? As the Beach Boys would say: “God only knows”

.

Good read; clear and to the point! Great to come back to the basics of theory in times when people tend to overcomplicate.